Narrating books is much more interesting than canned speech therapy exercises. As we read from several books a day, Pamela has many opportunities to practice the art of speaking during the day. Some books are above her reading level, but she still finds ways to narrate. I remember reading biographies about autistic people who were bored silly in school because they were secretly reading, but still being taught their alphabet in class. I never want to underestimate Pamela, and I want her to tackle to our rich literary heritage. I would rather err on the side of going above her level, rather than dumbing down her material, and I assume that, if she understood nothing, she would balk and have meltdowns every time we open a book. As she continues to seem eager for reading, I hope I have found a proper balance between easy and challenging books.

We just finished reading Mary Emma and Company by Ralph Moody, the fourth in a series about Ralph's family. I believe this is right at Pamela's reading level. I asked Pamela to narrate what she remembered from the book and this is what she said:

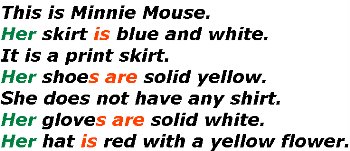

Ralph has a new house. His father died. He is in heaven. Ralph said, "Goodbye, Colorado! Hello, Massachusetts!" He has a stove. It got burned. They can make a better stove. It is beautiful.Pamela's narration seems immature. When she was four-years old, her developmental pediatrician told us she might not ever speak, much less read or write. On top of having autism, she has syntactic aphasia, or "difficulties in using words in the correct order and/or forms for effective communication" (page 3 of Teaching Language Deficient Children). Pamela, like others with aphasia, drops little words such as prepositions, conjunctions and articles: years ago she might have said, "fire Ralph" for "Ralph saw a fire." Her brain is not wired to spot grammatical patterns and apply them. For example, three weeks ago, she could not string together these words: "does not have any." Up until this point, she could manage, "has no." Last week, I introduced the new phrase into her multi-sensory language activities through written stories, listening and repeating, oral and written narration, copywork, and dictation. Now, she can say the phrase smoothly, but it will take another week or two for it to become part of her daily speech patterns.

Mother has some laundry. She can wash some clothes. Grace is helpful. Mother can dry clothes. They can fold clothes. They can make money.

Ralph saw a fire. A bridge was broken. He saw a fire chief. A fire chief can chop wood. Ralph got bridge logs.

A May basket is for church. It has some flowers. Grace got a basket. A basket is beautiful. A note is for happy Mother's Day. Mother is happy.

When put in perspective, Pamela’s oral narration of Mary Emma and Company is absolutely fabulous!