Before I launch into the joys of studied dictation, I thought I'd share two pictures of Pamela during her break. Below, you see her watching television. And to the left are the babies (NOT DOLLS) watching television with her. She put them there!

Before I launch into the joys of studied dictation, I thought I'd share two pictures of Pamela during her break. Below, you see her watching television. And to the left are the babies (NOT DOLLS) watching television with her. She put them there!

Charlotte Mason's method for teaching language arts is based upon child development. Rather than forcing paper skills on children at younger and younger ages, desperately hoping to give them a head start, she believed in laying a foundation for writing through oral language. In her first book, Home Education, her recommendations for children under the age of six are vastly different from that of older children because she believed in the outdoor life for the little ones. She required NO formal lessons for preschool and kindergarten. Zero. Zip. NADA!

In those tender years, she focused on oral language. She believed children ought to sharpen their speaking abilities by telling what they see in their explorations outside. An educator broadens vocabulary by supplying unfamiliar names for and parts of objects found by children and improves listening skills by sharing what she sees and asks thoughtful (not gotcha) questions. To hone articulation, she encouraged reciting sing-songs in English and another language. Those of you with children who struggle with fine motor skills or visual discrimination take note! There are no worksheets and no required reading. Those of you with kids who treat carpet squares like trampolines, there are no prolonged periods of sedentary boredom!

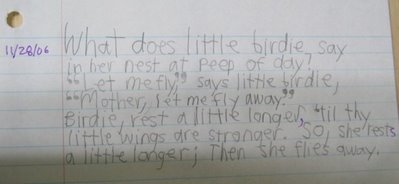

Charlotte recognized that some children under the age of six have a keen interest in letters and reading. She did not see anything wrong with teaching letters and their sounds to kids who were ready as long as it seemed like play and stopped when the child tired of it. She outlined reading lessons combining both phonics and sight words for children once they turned six. Six was not a hard and fast rule for some children bloom later (the appendix of School Education includes a narration by a child of age 7 3/4 in the lowest level class in her school). She also worked on the written expression of six-year olds through penmanship and, once they knew all of their letters, copywork from living books that they read. Copywork focuses attention on spelling, grammar, and punctuation and builds the foundation for learning the mechanics of writing. Here is an example of Pamela's copywork right now:

And, now, finally, I reach the topic of today's post: studied dictation. Charlotte Mason scaffolded the teaching of composition by introducing studied dictation only after children had nailed down copywork. Most children started when they turned eight. Early in my blog, I described how to do studied dictation and a sample spelling lesson. I love studied dictation because it is a fast, efficient way to teach writing mechanics! The following three-minute shows you how quickly you can do studied dictation (which we try to do daily).

When Pamela requested doing Eric Carle books this year, I agreed because some contain quite challenging words. We started off with The Very Hungry Caterpillar two weeks ago. I decided to have an English notebook to store Pamela's copywork, poems for recitation, and studied dictation. Here is the sheet Pamela studies, which doubles as a record of how she fared.

When Pamela requested doing Eric Carle books this year, I agreed because some contain quite challenging words. We started off with The Very Hungry Caterpillar two weeks ago. I decided to have an English notebook to store Pamela's copywork, poems for recitation, and studied dictation. Here is the sheet Pamela studies, which doubles as a record of how she fared. You can see in the page on the left the first eight days of writing were perfect! She made several mistakes on the ninth day, which contained many challenging words. I wrote a lesson focused on three errors: changing y to i when adding a suffix, listening to vowels in the middle of a multi-syllabic word, and contrasting long e at the end of English words versus Italian words. I wrap up the lesson with application of what was covered in the form of a caterpillar story as you can see below.

You can see in the page on the left the first eight days of writing were perfect! She made several mistakes on the ninth day, which contained many challenging words. I wrote a lesson focused on three errors: changing y to i when adding a suffix, listening to vowels in the middle of a multi-syllabic word, and contrasting long e at the end of English words versus Italian words. I wrap up the lesson with application of what was covered in the form of a caterpillar story as you can see below.

Clearly, my lesson was effective for Pamela did not make those mistakes again in her second attempt at this sentence. The next lesson covered the mistakes made on the tenth day: capitalizing words derived from the names of countries, listening to the ending of words, and placing a space between adjectives and nouns.

Clearly, my lesson was effective for Pamela did not make those mistakes again in her second attempt at this sentence. The next lesson covered the mistakes made on the tenth day: capitalizing words derived from the names of countries, listening to the ending of words, and placing a space between adjectives and nouns. As you can see, both lessons worked. Her third attempt was perfect!

As you can see, both lessons worked. Her third attempt was perfect!