Today Pamela and I delivered meals on wheels, and I became very mindful of how much she has changed in her ability to experience share. If I only assessed quantity (length of sentences and number of words), I might be disappointed because of her aphasia. The quality of her conversations are terrific. Persons with autism tend to speak in verbal stims or focus only on certain favorite topics. Pamela still does that to some extent and I see it most when she is feeling incompetent or upset. It is her way of calming down and reassuring herself.

This morning the third stop on our list caused Pamela to scream. We walked to the apartment, and the gentlemen was sitting outside in a chair. So far so good. There was another man inside his place cleaning, and it was absolutely empty, not one stick of furniture. On the ground near the sidewalk was a large sheet of broken glass. After her squeal, I reassured her that everything was fine. I gave the meal to the man, and he explained that he was moving to another apartment in the complex. Pamela pointed to him and said, "No! You're not moving." He told her that he was, and we said good-bye. As we walked to the car, I told Pamela, "The man is moving over there." She looked and added, "Not leaving Manning." I replied, "Yep. He wants to be near his family."

We were getting near the end of our route and I decided to sign the sheet. I handed it to Pamela for her signature. She looked up at me surprised, "Are we done?" I answered, "No, we have two more stops." I did something out of the norm, so she commented on it, which is part of experience sharing. She could have waited to see what would happen but her curiosity drove her to ask.

As we were driving home Pamela pointed out the saucer magnolias blooming and asked, "What's that?" I answered her question and loved that she wanted to continue a conversation from yesterday. When we drove home from lunch, we noticed the signs of spring. I pointed out the flocks of robins and pink crepe myrtles blooming. She noticed the bright green grass in one of the fields. We are going to add our observations to nature notebooks.

We were almost home and here was another little gem:

Pamela: What about April?

Me: What about it?

Pamela: April 24

Me: Oh, Easter!

Pamela: It's late.

Me: You're right! It is late.

Pamela: What am I going to wear?

Me: I don't know!

Pamela: Short sleeves!

All of these questions were fresh like Spring. Pamela shared new thoughts that were emerging in her mind. They were important enough to her that she wanted to tell me. She reflected on the context of what we have been doing: delivering meals and looking for signs of Spring. She pondered what everything meant. She stayed in the moment. Isn't that grand?

P.S. It goes to show that one doesn't need to question, prompt, and correct to chat with a person with autism.

Showing posts with label scripting. Show all posts

Showing posts with label scripting. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

Thursday, May 10, 2007

Scripters Anonymous

One feature of autism that distinguishes it from a language disorder is echolalia (echoing memorized word patterns either immediately or much later). In the movie, Rainman, Raymond Babbitt rocked and repeated Abbot and Costello's "Who's on First?" skit to calm himself. Echolalia can be much more sophisticated than that. Pamela memorized whole chunks of word patterns and used them when she thought appropriate. For example, when she was five, she had memorized the mournful tone of Baloo in the Jungle Book, "Mowgli, Mowgli, come back!" and repeated it when she was sad and trying to comfort herself. This description fits what we saw:

Today, books are dedicated to teaching scripts that help autistic children learn to converse. This still would not have helped Pamela because she has a hard time memorizing scripts unless they are jazzed up for "viewers like you" (*ahem* a new scripted line). We did not figure out until recently that Pamela can memorize poetry with multi-sensory methods and have known for several years that meaningful progress in syntax comes in seven multi-sensory steps! Children who can memorize scripts can also become dependent upon the scripts and unsure of what to do with people who fail to follow the script. Thus, researchers have developed ways to fade scripts.

I am not a fan of the formal teaching of scripts, and I tend to concur with RDI's recommendation to avoid them. Anyone who has been sucked into scriptland knows that sense of helplessness as your sanity evaporates. We have tried a variety of techniques to teach flexibility: laughing at unexpected twists I made in the script, making her own twists, being silly with pauses, changes in pitch, sound effects, etc. Monkeying around with scripts taught Pamela to go with the flow and enjoy surprises.

One of Pamela's issues is that she does not always realize when she confuses people with references to her scripts. She has a couple of patient aunts who play along and that is it! Lately, I have been experimenting with ways to discourage scripting without discouraging Pamela from speaking and interacting with us.

* Ignoring It - Ignoring scripting is the least effective strategy in my experience. When I ignore Pamela, she gets annoyed and will repeat the script prompt followed by "Say it!" In this case, Pamela wagged her finger at me and badgered me. Ignoring her only intensified her nagging.

* Ignoring It - Ignoring scripting is the least effective strategy in my experience. When I ignore Pamela, she gets annoyed and will repeat the script prompt followed by "Say it!" In this case, Pamela wagged her finger at me and badgered me. Ignoring her only intensified her nagging.

* Sad Reaction - After she started wagging her finger, I become very quiet, stuck out my poochie lip, and looked down at my feet. Pamela did something splendid. She walked up to me, studied my face, smiled, and said, "Sad." Then, she abruptly transitioned to the locked box.

* Sad Reaction - After she started wagging her finger, I become very quiet, stuck out my poochie lip, and looked down at my feet. Pamela did something splendid. She walked up to me, studied my face, smiled, and said, "Sad." Then, she abruptly transitioned to the locked box.

* Springing off of It - Pamela started a Betty Crocker script, so I declared in off-script sentences, "We're just like Betty Crocker! You could be the Betty Crocker of gluten-free, casein-free." She clasped her hands and giggled with delight at my surprising comment.

* Springing off of It - Pamela started a Betty Crocker script, so I declared in off-script sentences, "We're just like Betty Crocker! You could be the Betty Crocker of gluten-free, casein-free." She clasped her hands and giggled with delight at my surprising comment.

* Adapting It - I adapt the script to her task. Pamela said, "You must be 18 or older to order." I ignored her, so she came back to it, "You must . . . I must . . ." She was stirring her batter, so I said, "stir and stir and stir." She laughed and giggled since she likes twisting scripts.

* Adapting It - I adapt the script to her task. Pamela said, "You must be 18 or older to order." I ignored her, so she came back to it, "You must . . . I must . . ." She was stirring her batter, so I said, "stir and stir and stir." She laughed and giggled since she likes twisting scripts.

* Distracting Her - Sometimes, I can distract Pamela by gasping and turning my gaze to the next step in whatever we are doing. I have also succeeded by using declarative language to switch topics completely. In this case, I started talking about the need to stir the batter thoroughly until all the dry ingredients to become wet. Later, Pamela was stuck on her, "You must . . . " prompt. We had just added the pecans, so I asked her about her preference on how to say this nut, "Pamela, do you prefer PEE-can or pe-CAHN?" She persisted, so I added, "You must . . . eat . . . PECAAAHHNNNSSS!"

* Distracting Her - Sometimes, I can distract Pamela by gasping and turning my gaze to the next step in whatever we are doing. I have also succeeded by using declarative language to switch topics completely. In this case, I started talking about the need to stir the batter thoroughly until all the dry ingredients to become wet. Later, Pamela was stuck on her, "You must . . . " prompt. We had just added the pecans, so I asked her about her preference on how to say this nut, "Pamela, do you prefer PEE-can or pe-CAHN?" She persisted, so I added, "You must . . . eat . . . PECAAAHHNNNSSS!"

* Saying the Wrong Thing - I often say something wrong to encourage flexibility. She was stuck on the "You must" train, so I said, "Eat spinach." She prompted, "You must be" and I returned, "29!" We have been doing this for years, so she loves when I say the wrong things.

* Saying the Wrong Thing - I often say something wrong to encourage flexibility. She was stuck on the "You must" train, so I said, "Eat spinach." She prompted, "You must be" and I returned, "29!" We have been doing this for years, so she loves when I say the wrong things.

* Reacting to Her Script Twists - Sometimes, she twists her own script as a joke. This time, she said, "You must be 18 to . . ." while reaching for a utensil. She paused and glanced at me to see my reaction when she sneakily added, "die". Pamela is about the happiest person you will ever meet and not morbid about death. I think she was trying to surprise me with something entirely unexpected. I exaggerated my reaction by covering my mouth and said, "Nooooo! We don't want that to happen. You made a joke! That was a joke!" Then she confirmed it by saying, "Only to order!"

* Reacting to Her Script Twists - Sometimes, she twists her own script as a joke. This time, she said, "You must be 18 to . . ." while reaching for a utensil. She paused and glanced at me to see my reaction when she sneakily added, "die". Pamela is about the happiest person you will ever meet and not morbid about death. I think she was trying to surprise me with something entirely unexpected. I exaggerated my reaction by covering my mouth and said, "Nooooo! We don't want that to happen. You made a joke! That was a joke!" Then she confirmed it by saying, "Only to order!"

Echolalia is reflective of how the child processes information. The child with autism processes information as a whole "chunk" without processing the individual words that comprise the utterance. In processing these unanalyzed "chunks" of verbal information, many children with autism also process part of the context in which these words were stated, including sensory and emotional details. Some common element from this original situation is then triggered in the current situation which elicits the child's echolalic utterance.We first started addressing Pamela's language way back in 1991, when she was two years old. We could not find much information because Pamela was at the beginning of increase in the rate of autism. We had to improvise while we kept on top of emerging research and started Pamela off with sign language. When her echolalia emerged, we opted to mold it and use it, rather than discourage it. For example, Pamela picked up one phrase "It's Sunday" advertising a show aired on that day of the week. Every day, we would use that phrase "It's _______". Then, when she could do that, we would work on negation "It's not _______". After that, we twisted it to, "Yesterday was ________" and "Tomorrow's _______". We eventually transitioned to months and seasons. One little jingle afforded a great deal of mileage. This word pattern started out as a stim and, as such gave us many opportunities to practice new language.

Today, books are dedicated to teaching scripts that help autistic children learn to converse. This still would not have helped Pamela because she has a hard time memorizing scripts unless they are jazzed up for "viewers like you" (*ahem* a new scripted line). We did not figure out until recently that Pamela can memorize poetry with multi-sensory methods and have known for several years that meaningful progress in syntax comes in seven multi-sensory steps! Children who can memorize scripts can also become dependent upon the scripts and unsure of what to do with people who fail to follow the script. Thus, researchers have developed ways to fade scripts.

I am not a fan of the formal teaching of scripts, and I tend to concur with RDI's recommendation to avoid them. Anyone who has been sucked into scriptland knows that sense of helplessness as your sanity evaporates. We have tried a variety of techniques to teach flexibility: laughing at unexpected twists I made in the script, making her own twists, being silly with pauses, changes in pitch, sound effects, etc. Monkeying around with scripts taught Pamela to go with the flow and enjoy surprises.

One of Pamela's issues is that she does not always realize when she confuses people with references to her scripts. She has a couple of patient aunts who play along and that is it! Lately, I have been experimenting with ways to discourage scripting without discouraging Pamela from speaking and interacting with us.

* Ignoring It - Ignoring scripting is the least effective strategy in my experience. When I ignore Pamela, she gets annoyed and will repeat the script prompt followed by "Say it!" In this case, Pamela wagged her finger at me and badgered me. Ignoring her only intensified her nagging.

* Ignoring It - Ignoring scripting is the least effective strategy in my experience. When I ignore Pamela, she gets annoyed and will repeat the script prompt followed by "Say it!" In this case, Pamela wagged her finger at me and badgered me. Ignoring her only intensified her nagging. * Sad Reaction - After she started wagging her finger, I become very quiet, stuck out my poochie lip, and looked down at my feet. Pamela did something splendid. She walked up to me, studied my face, smiled, and said, "Sad." Then, she abruptly transitioned to the locked box.

* Sad Reaction - After she started wagging her finger, I become very quiet, stuck out my poochie lip, and looked down at my feet. Pamela did something splendid. She walked up to me, studied my face, smiled, and said, "Sad." Then, she abruptly transitioned to the locked box. * Springing off of It - Pamela started a Betty Crocker script, so I declared in off-script sentences, "We're just like Betty Crocker! You could be the Betty Crocker of gluten-free, casein-free." She clasped her hands and giggled with delight at my surprising comment.

* Springing off of It - Pamela started a Betty Crocker script, so I declared in off-script sentences, "We're just like Betty Crocker! You could be the Betty Crocker of gluten-free, casein-free." She clasped her hands and giggled with delight at my surprising comment. * Adapting It - I adapt the script to her task. Pamela said, "You must be 18 or older to order." I ignored her, so she came back to it, "You must . . . I must . . ." She was stirring her batter, so I said, "stir and stir and stir." She laughed and giggled since she likes twisting scripts.

* Adapting It - I adapt the script to her task. Pamela said, "You must be 18 or older to order." I ignored her, so she came back to it, "You must . . . I must . . ." She was stirring her batter, so I said, "stir and stir and stir." She laughed and giggled since she likes twisting scripts. * Distracting Her - Sometimes, I can distract Pamela by gasping and turning my gaze to the next step in whatever we are doing. I have also succeeded by using declarative language to switch topics completely. In this case, I started talking about the need to stir the batter thoroughly until all the dry ingredients to become wet. Later, Pamela was stuck on her, "You must . . . " prompt. We had just added the pecans, so I asked her about her preference on how to say this nut, "Pamela, do you prefer PEE-can or pe-CAHN?" She persisted, so I added, "You must . . . eat . . . PECAAAHHNNNSSS!"

* Distracting Her - Sometimes, I can distract Pamela by gasping and turning my gaze to the next step in whatever we are doing. I have also succeeded by using declarative language to switch topics completely. In this case, I started talking about the need to stir the batter thoroughly until all the dry ingredients to become wet. Later, Pamela was stuck on her, "You must . . . " prompt. We had just added the pecans, so I asked her about her preference on how to say this nut, "Pamela, do you prefer PEE-can or pe-CAHN?" She persisted, so I added, "You must . . . eat . . . PECAAAHHNNNSSS!" * Saying the Wrong Thing - I often say something wrong to encourage flexibility. She was stuck on the "You must" train, so I said, "Eat spinach." She prompted, "You must be" and I returned, "29!" We have been doing this for years, so she loves when I say the wrong things.

* Saying the Wrong Thing - I often say something wrong to encourage flexibility. She was stuck on the "You must" train, so I said, "Eat spinach." She prompted, "You must be" and I returned, "29!" We have been doing this for years, so she loves when I say the wrong things.  * Reacting to Her Script Twists - Sometimes, she twists her own script as a joke. This time, she said, "You must be 18 to . . ." while reaching for a utensil. She paused and glanced at me to see my reaction when she sneakily added, "die". Pamela is about the happiest person you will ever meet and not morbid about death. I think she was trying to surprise me with something entirely unexpected. I exaggerated my reaction by covering my mouth and said, "Nooooo! We don't want that to happen. You made a joke! That was a joke!" Then she confirmed it by saying, "Only to order!"

* Reacting to Her Script Twists - Sometimes, she twists her own script as a joke. This time, she said, "You must be 18 to . . ." while reaching for a utensil. She paused and glanced at me to see my reaction when she sneakily added, "die". Pamela is about the happiest person you will ever meet and not morbid about death. I think she was trying to surprise me with something entirely unexpected. I exaggerated my reaction by covering my mouth and said, "Nooooo! We don't want that to happen. You made a joke! That was a joke!" Then she confirmed it by saying, "Only to order!"

Friday, October 13, 2006

Snoopy Dancing in Carolina!

Pamela amazed me today! This morning, she rifled through my drawer, looking at wrapping paper. She folded a small piece around an extra copy of the book Stuart Little and announced her intention to give a present to Amy, one of my algebra students. What a sweet gesture! Amy, a fellow E.B. White fan, beamed when Pamela handed her the present when we met for algebra.

After algebra, my goal was to practice the A-Q/A-Q way of conversing. Before the speech session, I wrote the title "What's your favorite. . ." on a piece of paper and placed the words "year?" "color?" "food?" "month?" "season?" "book?" in a column. I instructed Amy to repeat back whatever questions Pamela asked, and I recorded their replies.

Pamela easily answered Amy's questions, but needed some help keeping the conversation going. I prompted her to continue with the next question in the column until we reached seasons. Amy replied, "My favorite season is winter because I like to ski in West Virginia." Suddenly, Pamela began asking very appropriate questions about that state, "Where's West Virginia?" followed by "Who's in West Virginia?" Amy does not know anyone in the mountain state, so I prompted Pamela to ask, "What's in West Virginia?" and Amy supplied the name of her favorite ski resort. When we reached the end of the list, Pamela smiled and said, "Goodbye!" for she was ready to head home. Ending the week on such a promising note tickled me to death!

After algebra, my goal was to practice the A-Q/A-Q way of conversing. Before the speech session, I wrote the title "What's your favorite. . ." on a piece of paper and placed the words "year?" "color?" "food?" "month?" "season?" "book?" in a column. I instructed Amy to repeat back whatever questions Pamela asked, and I recorded their replies.

Pamela easily answered Amy's questions, but needed some help keeping the conversation going. I prompted her to continue with the next question in the column until we reached seasons. Amy replied, "My favorite season is winter because I like to ski in West Virginia." Suddenly, Pamela began asking very appropriate questions about that state, "Where's West Virginia?" followed by "Who's in West Virginia?" Amy does not know anyone in the mountain state, so I prompted Pamela to ask, "What's in West Virginia?" and Amy supplied the name of her favorite ski resort. When we reached the end of the list, Pamela smiled and said, "Goodbye!" for she was ready to head home. Ending the week on such a promising note tickled me to death!

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Navigating Questions & Answers

I am tailoring Navigating the Social World to guide activities for conversational practice. The focus is on communication and social skills (Section Two), namely basic conversational responses. At home, Pamela is adept at asking and answering questions about her enthusiasms (calendars, The Hoober-Bloob Highway, and Mario and Luigi Superstar Saga). She can ask and answer simple questions already mastered at her present level in personal description stories (see page 14) with people in the family. She needs to work on following up a statement (with either a statement or question).

I want Pamela to leave each session flush with success and joy, so I limit conversations to her interests and sentence structures she can easily do: answer and ask yes-no questions. The first time Pamela and Amy took turns asking each other what states they had visited, "Did you see Alaska?" I noticed that Pamela struggled with following up her answer by asking question. She needed prompting to continue the conversation even though it was a repetition of the same question. Clearly she had difficulties switching roles.

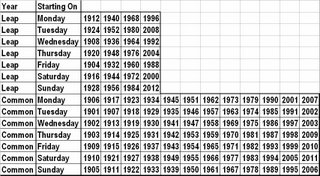

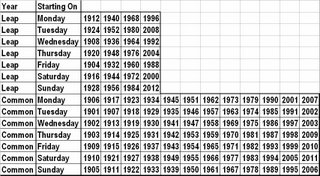

The second time I turned the conversation into a riddle game to simplify the conversation structure. Amy would pick a year, and Pamela would ask questions like "Is it a leap year?" or "Does it start Monday?" until she guessed the year. Then we reversed the tables: Pamela would pick a year and Amy asked her questions. Amy and I both needed a cheat sheet I made in Excel as a crutch. Pamela sees the calendar in her head and needs no crutch. When reading history books, she will often tell us the day of the week an event occurred. Pamela reveled playing a calendar game with another teen, and Amy was amazed at Pamela's savant skill.

The third time we played the riddle game, but focused on the topic of animals. Both Amy and Pamela share an interest in animals. Pamela was highly animated, and her face lit up whenever she or Amy solved the riddle. Clearly, she succeeds at Q/A/Q/A types of conversations in which one person always asks the question and one person always answers it. She has no problem being either the questioner or answerer as long as it is consistent during the conversation. At home, I plan to vary the conversations to get her used to A-Q/A-Q so that the person answering a question continues with a new question.

I want Pamela to leave each session flush with success and joy, so I limit conversations to her interests and sentence structures she can easily do: answer and ask yes-no questions. The first time Pamela and Amy took turns asking each other what states they had visited, "Did you see Alaska?" I noticed that Pamela struggled with following up her answer by asking question. She needed prompting to continue the conversation even though it was a repetition of the same question. Clearly she had difficulties switching roles.

The second time I turned the conversation into a riddle game to simplify the conversation structure. Amy would pick a year, and Pamela would ask questions like "Is it a leap year?" or "Does it start Monday?" until she guessed the year. Then we reversed the tables: Pamela would pick a year and Amy asked her questions. Amy and I both needed a cheat sheet I made in Excel as a crutch. Pamela sees the calendar in her head and needs no crutch. When reading history books, she will often tell us the day of the week an event occurred. Pamela reveled playing a calendar game with another teen, and Amy was amazed at Pamela's savant skill.

The third time we played the riddle game, but focused on the topic of animals. Both Amy and Pamela share an interest in animals. Pamela was highly animated, and her face lit up whenever she or Amy solved the riddle. Clearly, she succeeds at Q/A/Q/A types of conversations in which one person always asks the question and one person always answers it. She has no problem being either the questioner or answerer as long as it is consistent during the conversation. At home, I plan to vary the conversations to get her used to A-Q/A-Q so that the person answering a question continues with a new question.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)