We are blessed to have part-time and full-time students in the autism spectrum at our school. I think Grandin might like our approach to science and art by the scenic trail of nature study. The primary and elementary classes are reading Minn of the Mississippi by Holling C. Hollings. To help them feel the "realness" of the story, I shared pictures of my family's visit to the headwaters of the Mississippi at Itasca State Park about ten years ago.

We are blessed to have part-time and full-time students in the autism spectrum at our school. I think Grandin might like our approach to science and art by the scenic trail of nature study. The primary and elementary classes are reading Minn of the Mississippi by Holling C. Hollings. To help them feel the "realness" of the story, I shared pictures of my family's visit to the headwaters of the Mississippi at Itasca State Park about ten years ago.

Some autistic students develop the habit of frustration for a variety of reasons. It takes time to help them find joy in learning what is beyond their pet interests. Every person is different, so what works for one autie may not inspire another.

Eman is teaching me so much. He often refuses to try because either "it's too hard" or "he's bored." He does not enjoy keeping a nature notebook until he finds something that delights him, in which case he begs to draw. One day when he was dragging his feet, I let him tape pictures to a page and narrate what I should write. Novelty is a big hook for him, and being able to use double-sided tape for the first time made a few notebooking experiences positive. When that novelty wore off, I tapped into a positive episodic memory of last year when he joined us for the turtle release party. I showed him pictures of those very turtles: the cage my friend constructed to protect them from crows, the nest, the hatchlings, and the dud.

When the classroom after lunch was too much for him, we switched to reading Minn in the morning. We focused on finding joy in his tasks. When he wanted to draw a story about Minn in his silly notebook (comic strip things that make him laugh), I encouraged him to start an unsilly notebook (comic strip things related to what he is learning). When he asked to read outside on a sunny day, I agreed if he promised to do his best on the notebook. And, he did! One day, he drew seven different scenes representing the most emotional moments of Minn's life: her hatching, getting her leg shot off, her canoe ride, meeting the fox, scaring the boys in the pond, laying eggs, and snapping at the dog's tail.

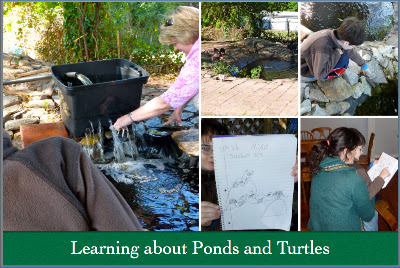

Right now, working on the pond gives him joy. Watching what happens when we turn on the water pump that pushes water through our homemade water filter is exciting. We stand at the little pool and watch it with anticipation until the water reaches the top of the stones and forms a waterfall. One day, the filter overflowed and he watched the headmaster solve the problem. Somehow, cleaning leaves out of the pond gets him to thinking about turtles. Before long, he is ready to read more about Minn's adventures, draw it in his unsilly notebook, and read it to his mother.

On another day, a cockroach caught his eye. He was shocked when I shared my plans to draw it in my nature notebook. "You keep one, too?" He was so interested in seeing mine that I promised he could look through it once he had finished making an entry in his.

On another day, a cockroach caught his eye. He was shocked when I shared my plans to draw it in my nature notebook. "You keep one, too?" He was so interested in seeing mine that I promised he could look through it once he had finished making an entry in his.

At another time, two doves enchanted us with a stroll around the little pool to get a sip of water.

Speaking of problem-solving, Grandin spotlighted another value of hands-on projects: "Practical things do not always work right and people skilled in the real world learn how to improvise. When I made a mistake on a sewing project, I was sometimes able to fix it and other times I could not. Mistakes I made cutting the fabric wrong on a sewing project taught me that I had to slow down. I had to be more careful before I cut the material."

One day, he helped his class with the compost bin. The lesson screeched to a halt when they discovered worms. He watched the students find grubs and toss them into the pond to feed the fish. Two weeks later, his cat showed up at school. He decided to see if she would eat a worm and he knew exactly where to find them. The cat did not!

One day, he helped his class with the compost bin. The lesson screeched to a halt when they discovered worms. He watched the students find grubs and toss them into the pond to feed the fish. Two weeks later, his cat showed up at school. He decided to see if she would eat a worm and he knew exactly where to find them. The cat did not!

And, then, there was the day he found the dead fish. Eman studied it in the net for quite some time. He wanted to touch it but was afraid he might get cut. So, I offered to do it first. A bit grossed out, I put my finger on it for only an instant. "No, you need to do it longer!" So, I held my finger on the squishy fish and it must have been long enough. He mustered his courage and touched it himself.

Mason's thoughts in connection to literary books like Minn of the Mississippi: "The approach to science as to other subjects should be more or less literary, that the principles which underlie science are at the same time so simple, so profound and so far-reaching that the due setting forth of these provokes what is almost an emotional response" (Pages 218-219).

Mason's thoughts in connection to outdoor work: "They are expected to do a great deal of out-of-door work... They keep records and drawings in a Nature Note Book and make special studies of their own for the particular season with drawings and notes" (Page 219).

Mason's thoughts on nature notebooks: "The nature note book is very catholic and finds room for the stars in their courses and for, say, the fossil anemone found on the beach at Whitby. Certainly these note books do a good deal to bring science within the range of common thought and experience; we are anxious not to make science a utilitarian subject" (Page 223).