I did a special needs presentation on assessing therapies from a Charlotte Mason perspective. You can find the audio and handout here. I prepared the following four videos for my talk.

Saturday, June 30, 2007

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

The Road Less Traveled Part II

Whenever we travel, I try to find places to visit related to Ambleside Online books. We have been in Caddie Woodlawn's actual house and a replica of Laura's cabin in the Big Woods, at Lake Itasca where Minn of the Mississippi hatched, and Fort Harrod where Stephanie Venable bought supplies and no copies of Tree of Freedom were to be had (shocking!). We even spent two years in an Alaskan fishing village very much like the setting of Gentle Ben. Tuskegee was on the way to Louisiana so we wanted to supplement our sense of place for Unshakable Faith (our George Washington Carver biography). Steve, a stamp collector, was excited to learn more about two historical figures immortalized by the postal service (Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver).

Since both David and Steve are airplane fanatics, we first stopped at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic site. We were all fascinated to learn more about the story of these pioneering men. Steve and I are both Navy veterans decades after African-Americans became an integral part of our military. We learned many fascinating things like the fact that the government conceived of this idea before the United States entered the war (in 1939). The training program involved over 10,000 men and women because they trained as pilots, navigators, ordinancemen, mechanics, etc. between 1942 and 1946. They trained over 1,000 aviators for the war. No one knows why they choose the color red for the tail of their planes, but rumor has it was the only color in plentiful supply. (As the daughter of a Navy supply officer, I would not be surprised.) They distinguished themselves in combat in North Africa, Sicily, and the Mediterranean, and the military proclaimed the "experiment" a success, integrating the armed forces starting in 1948.

Since both David and Steve are airplane fanatics, we first stopped at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic site. We were all fascinated to learn more about the story of these pioneering men. Steve and I are both Navy veterans decades after African-Americans became an integral part of our military. We learned many fascinating things like the fact that the government conceived of this idea before the United States entered the war (in 1939). The training program involved over 10,000 men and women because they trained as pilots, navigators, ordinancemen, mechanics, etc. between 1942 and 1946. They trained over 1,000 aviators for the war. No one knows why they choose the color red for the tail of their planes, but rumor has it was the only color in plentiful supply. (As the daughter of a Navy supply officer, I would not be surprised.) They distinguished themselves in combat in North Africa, Sicily, and the Mediterranean, and the military proclaimed the "experiment" a success, integrating the armed forces starting in 1948.

The most shocking aspect is the rest of the story. After the government disbanded the training program in 1946, they closed off Moton Airfield and let it sit for forty-four years--untouched! All the important buildings still stand today, except for Hangar 2, which burned down in the 1970s. Nothing was done about it until after 1998 when it became a national historic site. Right now, a crew is restoring these historic buildings, most of which will be ready for visitors in October 2008. Here are photographs of Moton Field, including a Navy plane that we suspect is a T-2 Buckeye training jet that once belonged to VT-10 (a training squadron out of Pensacola, Florida).

Our next stop was the Tuskegee Institute, founded by former slave Booker T. Washington in 1881 with the backing of a former slave and a former slave owner. He was only twenty-four years old when he accepted the position. We explored the George Carver Museum, which houses historical artifacts and knowledge about Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington, and George Washington Carver. What fascinated me the most was how Booker T. Washington started with $2,000 per year for teachers' salaries: he had no money for books, supplies, buildings, etc. By securing financial backers from the North and through the hard work of teachers and students, they worked as a team to make that campus. The teachers and students cleared the land, grew vegetable gardens, made their own bricks, and built the buildings! His vision was for the school to be useful to the students and the community. The school developed a wagon with teaching materials that they took into the towns in the area to teach men and women important skills to better themselves (such as growing their own vegetable gardens to save on the cost of food) and to enrich themselves (such as products they could market: baskets, furniture, needlework, etc.). He deemphasized the liberal education so cherished by Charlotte Mason, and I was disappointed about that aspect of his philosophy. But, he clearly had a vision for his school and, like Charlotte, he changed the lives of so many people for the better. One interesting thing about a film we watched about his life--they were very balanced in bringing out controversial aspects of his life.

George Washington Carver was the kind of life-long learner Charlotte admired. Everyone knows he was a botanist and scientist who taught at Tuskegee. He also drew the most wonderful sketches and painted well. He crocheted, knitted, and did needlework, dying his own materials with natural pigments! He even extracted pigments from local clay to invent paint products for local farmers to beautify their homes. He recited poetry and one display has an audio recording of him reciting his favorite poem, "Equipment" by Edgar Guest. Like Charlotte, he devoted his life to education, wrote about a variety of topics, found a creative way to teach those who could not attend Tuskegee Institute, and never married. He took long walks in the countryside and saw Mr. Creator speak to him through nature. He encouraged his students to figure things out for themselves ala masterly inactivity and led the way through his own research. He possessed a living mind we hope all of our students have!

What did we do in the car? Steve drove, I crocheted, David read, and Pamela played her Gameboy. We managed to find a Starbucks in Jackson, Mississippi! We listened to more eclectic music: Mozart, Jesus Christ Superstar, and The Very Best of Cat Stevens plus all the stuff from yesterday.

Since both David and Steve are airplane fanatics, we first stopped at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic site. We were all fascinated to learn more about the story of these pioneering men. Steve and I are both Navy veterans decades after African-Americans became an integral part of our military. We learned many fascinating things like the fact that the government conceived of this idea before the United States entered the war (in 1939). The training program involved over 10,000 men and women because they trained as pilots, navigators, ordinancemen, mechanics, etc. between 1942 and 1946. They trained over 1,000 aviators for the war. No one knows why they choose the color red for the tail of their planes, but rumor has it was the only color in plentiful supply. (As the daughter of a Navy supply officer, I would not be surprised.) They distinguished themselves in combat in North Africa, Sicily, and the Mediterranean, and the military proclaimed the "experiment" a success, integrating the armed forces starting in 1948.

Since both David and Steve are airplane fanatics, we first stopped at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic site. We were all fascinated to learn more about the story of these pioneering men. Steve and I are both Navy veterans decades after African-Americans became an integral part of our military. We learned many fascinating things like the fact that the government conceived of this idea before the United States entered the war (in 1939). The training program involved over 10,000 men and women because they trained as pilots, navigators, ordinancemen, mechanics, etc. between 1942 and 1946. They trained over 1,000 aviators for the war. No one knows why they choose the color red for the tail of their planes, but rumor has it was the only color in plentiful supply. (As the daughter of a Navy supply officer, I would not be surprised.) They distinguished themselves in combat in North Africa, Sicily, and the Mediterranean, and the military proclaimed the "experiment" a success, integrating the armed forces starting in 1948.The most shocking aspect is the rest of the story. After the government disbanded the training program in 1946, they closed off Moton Airfield and let it sit for forty-four years--untouched! All the important buildings still stand today, except for Hangar 2, which burned down in the 1970s. Nothing was done about it until after 1998 when it became a national historic site. Right now, a crew is restoring these historic buildings, most of which will be ready for visitors in October 2008. Here are photographs of Moton Field, including a Navy plane that we suspect is a T-2 Buckeye training jet that once belonged to VT-10 (a training squadron out of Pensacola, Florida).

Our next stop was the Tuskegee Institute, founded by former slave Booker T. Washington in 1881 with the backing of a former slave and a former slave owner. He was only twenty-four years old when he accepted the position. We explored the George Carver Museum, which houses historical artifacts and knowledge about Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington, and George Washington Carver. What fascinated me the most was how Booker T. Washington started with $2,000 per year for teachers' salaries: he had no money for books, supplies, buildings, etc. By securing financial backers from the North and through the hard work of teachers and students, they worked as a team to make that campus. The teachers and students cleared the land, grew vegetable gardens, made their own bricks, and built the buildings! His vision was for the school to be useful to the students and the community. The school developed a wagon with teaching materials that they took into the towns in the area to teach men and women important skills to better themselves (such as growing their own vegetable gardens to save on the cost of food) and to enrich themselves (such as products they could market: baskets, furniture, needlework, etc.). He deemphasized the liberal education so cherished by Charlotte Mason, and I was disappointed about that aspect of his philosophy. But, he clearly had a vision for his school and, like Charlotte, he changed the lives of so many people for the better. One interesting thing about a film we watched about his life--they were very balanced in bringing out controversial aspects of his life.

George Washington Carver was the kind of life-long learner Charlotte admired. Everyone knows he was a botanist and scientist who taught at Tuskegee. He also drew the most wonderful sketches and painted well. He crocheted, knitted, and did needlework, dying his own materials with natural pigments! He even extracted pigments from local clay to invent paint products for local farmers to beautify their homes. He recited poetry and one display has an audio recording of him reciting his favorite poem, "Equipment" by Edgar Guest. Like Charlotte, he devoted his life to education, wrote about a variety of topics, found a creative way to teach those who could not attend Tuskegee Institute, and never married. He took long walks in the countryside and saw Mr. Creator speak to him through nature. He encouraged his students to figure things out for themselves ala masterly inactivity and led the way through his own research. He possessed a living mind we hope all of our students have!

What did we do in the car? Steve drove, I crocheted, David read, and Pamela played her Gameboy. We managed to find a Starbucks in Jackson, Mississippi! We listened to more eclectic music: Mozart, Jesus Christ Superstar, and The Very Best of Cat Stevens plus all the stuff from yesterday.

Monday, June 25, 2007

The Road Less Traveled

We are on vacation, heading to Louisiana. Rather than drive the interstate at break-neck speed, we decided to take our time and get to know the areas through which we drive. We spent yesterday, the first day of our vacation, on United States Route 301 and United States Route 80.

The passing scenery was fascinating. The part of 301 we drove is nowhere near the interstate. We enjoyed seeing old homes that were still receiving tender-loving care and winced at the formerly beautiful homes that were falling apart. We felt like we were in a time capsule because we could see how 301 was once the highway of choice. Old motels (long one-story things with two wings at an angle) were either crumbling or for sale. Few survived the building of Interstate 95 in the 1950s. We could see old diners, broken down gas stations, and cinder block buildings that were no more--Happy Days turned ghost town. We eyed homes with new metal roofs (as we are planning to replace our roof with a metal one next year). We saw egrets near the side of the road and one dead doe.

We decided to tighten our belts and find a place to eat after we crossed the border into Georgia. That happened at 1:15 and, as we drove from one quaint town to the next, we struggled to find a restaurant that was actually open. We meandered around Statesboro, but were obviously not in the food side of town. There was nothing that we could find open in Sylvania, Portal, or Twin City either. All of these cities are quaint, picturesque but cute does not cut it when your stomach is running on empty. By 2:30, we finally reached our oasis in the desert: Swainsboro. Our first thought was to hit the colleges because surely food would be plentiful. Wrong! After about five or six wrong turns, we realized the interstate is the thing and, once we headed toward the direction Interstate 20, restaurants appeared on the horizon like a mirage. Finally, restaurants! Not just one hole-in-the-wall, but a plethora of restaurants from which we could find foods Pamela could eat. We practically staggered into the DQ, eyes blinking tears of joy, and ordered everything on the menu. It was not until three o'clock that onion rings crossed my lips!

The big surprise was Dublin, Georgia. Driving down Bellevue Avenue, which doubles as United States Route 80, was spectacular. Classic Greek revival homes, Victorian homes with cupolas and bay windows, gingerbread houses, some with decorative and tasteful trim, stately old churches, lined this road, known as Millionaire Row. Most are mansions that cotton built. We would have missed all this had we drove the interstate!

Here are our lessons learned:

* The farther away you are from the interstate the least likely you are to find food, especially on a Sunday in Georgia with the blue laws in full force.

* Gas is twenty cents cheaper per gallon in South Carolina than it is in Georgia.

* South Carolina's mile markers are righteous (they advance one mile every mile), while Georgia's markers are despicable, resetting back to zero at the county line. (How does one calculate miles to the state border in Georgia?)

* Just because a city has a Home Depot does not mean it has a Starbucks.

* The interstate is faster, but the roads less traveled have more personality. The lesser roads have fewer cases of road rage and hardly any truckers.

Here is the music we played on the drive: Beatles One, The Best of George Harrison, Celine Dion, Topsy-Turvy, The Best of Gilbert and Sullivan, The Sound of Music, Nutcracker Suite, Cool, and cheap, nameless compilations of music by decade (60s, 70s, 80s, and disco).

The passing scenery was fascinating. The part of 301 we drove is nowhere near the interstate. We enjoyed seeing old homes that were still receiving tender-loving care and winced at the formerly beautiful homes that were falling apart. We felt like we were in a time capsule because we could see how 301 was once the highway of choice. Old motels (long one-story things with two wings at an angle) were either crumbling or for sale. Few survived the building of Interstate 95 in the 1950s. We could see old diners, broken down gas stations, and cinder block buildings that were no more--Happy Days turned ghost town. We eyed homes with new metal roofs (as we are planning to replace our roof with a metal one next year). We saw egrets near the side of the road and one dead doe.

We decided to tighten our belts and find a place to eat after we crossed the border into Georgia. That happened at 1:15 and, as we drove from one quaint town to the next, we struggled to find a restaurant that was actually open. We meandered around Statesboro, but were obviously not in the food side of town. There was nothing that we could find open in Sylvania, Portal, or Twin City either. All of these cities are quaint, picturesque but cute does not cut it when your stomach is running on empty. By 2:30, we finally reached our oasis in the desert: Swainsboro. Our first thought was to hit the colleges because surely food would be plentiful. Wrong! After about five or six wrong turns, we realized the interstate is the thing and, once we headed toward the direction Interstate 20, restaurants appeared on the horizon like a mirage. Finally, restaurants! Not just one hole-in-the-wall, but a plethora of restaurants from which we could find foods Pamela could eat. We practically staggered into the DQ, eyes blinking tears of joy, and ordered everything on the menu. It was not until three o'clock that onion rings crossed my lips!

The big surprise was Dublin, Georgia. Driving down Bellevue Avenue, which doubles as United States Route 80, was spectacular. Classic Greek revival homes, Victorian homes with cupolas and bay windows, gingerbread houses, some with decorative and tasteful trim, stately old churches, lined this road, known as Millionaire Row. Most are mansions that cotton built. We would have missed all this had we drove the interstate!

Here are our lessons learned:

* The farther away you are from the interstate the least likely you are to find food, especially on a Sunday in Georgia with the blue laws in full force.

* Gas is twenty cents cheaper per gallon in South Carolina than it is in Georgia.

* South Carolina's mile markers are righteous (they advance one mile every mile), while Georgia's markers are despicable, resetting back to zero at the county line. (How does one calculate miles to the state border in Georgia?)

* Just because a city has a Home Depot does not mean it has a Starbucks.

* The interstate is faster, but the roads less traveled have more personality. The lesser roads have fewer cases of road rage and hardly any truckers.

Here is the music we played on the drive: Beatles One, The Best of George Harrison, Celine Dion, Topsy-Turvy, The Best of Gilbert and Sullivan, The Sound of Music, Nutcracker Suite, Cool, and cheap, nameless compilations of music by decade (60s, 70s, 80s, and disco).

Sunday, June 24, 2007

I'm Bleeding! :-)

The other day, Pamela and I shared a wonderful, unplanned, unscripted moment! We were preparing for Pamela's narration, so I had the camera ready to go. When Pamela left the room to use the bathroom, she stubbed her toe. I knew she had bumped herself, but did not realize she had cut her toe. After she walked back into the homeschool room, I started up the camera. Before she launched into her narration, Pamela just had to tell me about her bleeding toe, which she had covered with ointment. Pamela interacted with me beautifully and laughed when I made a joke that was a play on the title of the story to be narrated, "Dee Finds Boo."

What makes RDI so difficult to explain are these little moments in life in which two people communicate on multiple levels with no real goal (such as getting the right answer or using the correct syntax). Sharing emotions like this is the difference between having friends and connecting with friends. In the RDI World, this is called experience sharing:

You can see we had two levels of communication going, both nonverbal and verbal. Pamela gives meaningful eye contact (not just a look because of prompting) and intiates the conversation. She invites me to interact with her facial expression. She wants me to know about her stubbed toe! When I react, she lifts her foot to show me her little wound, shifting her gaze between her foot and my face. She sweetly smiles when I pour on some sympathy and responds with her hand when I reach out to hold her hand and comfort her. She laughs at my pun and looks down and covers her face in amusement.

In case, you had a hard time following the verbal communication, I wrote a transcript.

Pamela says, "I'm bleeding."

I ask, "Did you cut your foot?"

Pamela answers, "Yes."

I remark, "Aw, let me see! Oooo, yes, and you did a clever job taking care of it! Wow, Pamela, that was good."

Pamela adds, "Yes."

I say, "I'm sorry about your foot. Mmmmm, poor Pamela hurt her foot. Do you want to tell me about Dee and Boo? Oh, Pamela has a boo-boo."

Pamela laughs with a genuine smile.

I ask, "Do you get my joke?"

Pamela replies, "Yes, Boo!"

I add, "Boo, you got my joke!

Pamela asks, "What?"

I say, "Okay, I'm ready for your story!"

Pamela replies, "Yes."

What makes RDI so difficult to explain are these little moments in life in which two people communicate on multiple levels with no real goal (such as getting the right answer or using the correct syntax). Sharing emotions like this is the difference between having friends and connecting with friends. In the RDI World, this is called experience sharing:

Sharing different perspectives, integrating multiple information channels and determining "good enough" levels of comprehension. Using language and non-verbal communication to express curiosity, invite others to interact, share perceptions and feelings and coordinate your actions with others.

You can see we had two levels of communication going, both nonverbal and verbal. Pamela gives meaningful eye contact (not just a look because of prompting) and intiates the conversation. She invites me to interact with her facial expression. She wants me to know about her stubbed toe! When I react, she lifts her foot to show me her little wound, shifting her gaze between her foot and my face. She sweetly smiles when I pour on some sympathy and responds with her hand when I reach out to hold her hand and comfort her. She laughs at my pun and looks down and covers her face in amusement.

In case, you had a hard time following the verbal communication, I wrote a transcript.

Pamela says, "I'm bleeding."

I ask, "Did you cut your foot?"

Pamela answers, "Yes."

I remark, "Aw, let me see! Oooo, yes, and you did a clever job taking care of it! Wow, Pamela, that was good."

Pamela adds, "Yes."

I say, "I'm sorry about your foot. Mmmmm, poor Pamela hurt her foot. Do you want to tell me about Dee and Boo? Oh, Pamela has a boo-boo."

Pamela laughs with a genuine smile.

I ask, "Do you get my joke?"

Pamela replies, "Yes, Boo!"

I add, "Boo, you got my joke!

Pamela asks, "What?"

I say, "Okay, I'm ready for your story!"

Pamela replies, "Yes."

Saturday, June 23, 2007

Improving Reading Comprehension (Reality)

I broke up Jennifer Spencer's breakout session entitled into three parts: Introduction, Model, and Reality. In the first two posts, I narrate her actual session, while, in this final post, I will describe how we are applying at home. The picture is my "Go Chart!" which I put on foamboard to make it extra sturdy since I lack a permanent spot for hanging it. I am test-driving it with David for his readings of Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to prepare him for the book Deadliest Monster. I am finding it the most useful for Pamela. Up until now, all of her "narrations" have all been pure descriptions for we did not introduce the syntax of present tense verbs (singular) until recently. Now that she is comfortable with speaking in present tense, she is ready to narrate in the true sense of the word. I had been praying how to teach her the art of the narration and I am finding the Go! Chart invaluable. (Thank-you, Lord, for answered prayer!)

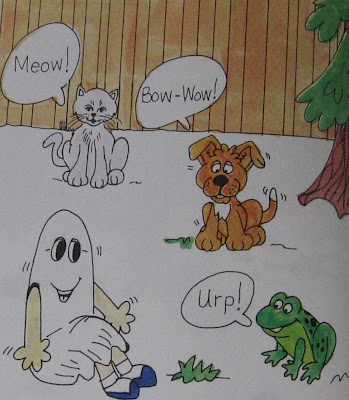

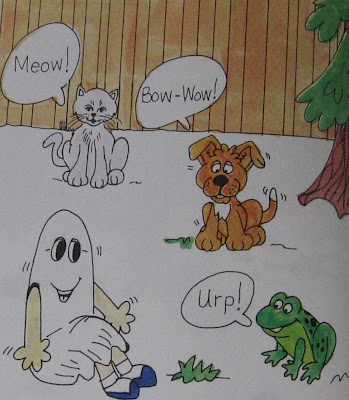

Every day, we focus on one very simple story from the syntax-controlled primers recommended by Dubard for the association method. While these are not living books, they are what Pamela needs to develop enough syntax to narrate living books. I see them as a bridge that helps her go from where she is to where I hope she will be. The first thing we do is to look at the story's words listed at the beginning of the primer (a discovery Pamela made!). In the story "Boo Jumps", the new words are animal sounds (urp, bow-wow, meow), and the reinforced words are many. Pamela also studies the title page, which is always illustrated. We record her predictions on one sticky note and predicted vocabulary on another before we ever read the story (you can click the picture to see it enlarged). In this story, Pamela predicts very reasonable possibilities: (1) Boo jumps, (2) Boo jumps on the fence, and (3) the animals can chase. She predicts words like fence, Boo, jumps, bow-wow, meow, and urp.

Then, she reads the story aloud to me one time (a single, hopefully attentive reading). After the reading, Pamela orally narrates the story. I film her to avoid slowing her down and listen to the recording to write it and post it on the board. As I write, I sort between sentences that are literal (drawn from the text or illustrations) and sentences that are interpretive. In this narration, Pamela incorrectly sequenced the story, placing Boo's jump before the animals making sounds. The frog makes a sound after the cat and dog jump on the fence (not before). This was the literal part of her narration:

Pamela included this bit of interpretive thinking in her narration:

I place a sticky note with her literal sentences in her narration in the column labeled Understanding and the inferred sentences under Interpretation. One weakness I have observed is that Pamela has difficulty ordering sentences in the correct sequence in her narrations, which is logical since she has difficulty in sequencing words because of her aphasia:

Once she finishes her oral narration, we study her predictions and line out any that were wrong. I make a point to congratulate her for thinking of such wonderful ideas. I am learning that Pamela is a champion at connecting these stories to her own life. This story reminded her of sitting in a tree when she was a little girl, and the dog reminded her of a dog we owned at that time of her life. Making connections comes naturally to Pamela. She makes hardly any connections to other books and stories, and that is what I will be encouraging whenever possible.

At this point of the process, we transition to how we have always done the association method. She and I read a script to practice new syntax and maintain mastered syntax: I read the questions and she, the answers; then, we swap roles; finally, I ask questions and she answers them without peeking. She does her copywork, written narration, and dictation plus worksheet activities that involve explaining why things belong in the same group, looking at a picture and writing her own questions and answers, filling in the blank and answering questions with the focus on correct syntax, and sequencing pictures from the story. Since Pamela finds sequencing difficult, I show her how to break up every story into a beginning, middle, and end. She is much better at sequencing during a narration when she fixes the story's arc in her mind.

The animals are the focus of the beginning of the story.

The middle is Boo's arrival and fall.

The story concludes with Boo and his friends sitting under the tree.

The final step of the Go! Chart is one last oral narration. Nearly every time, Pamela's narrations show great improvement in this final step. Pamela retells the story without peeking or looking at any pictures.

At this point, I often see ways to improve Pamela's narrations further. While she usually correctly sequences the big picture, the little details are sometimes in the wrong order. Borrowing an idea from Cheri Hedden, I type up the narration, one sentence per line. Then, I cut it into strips, one sentence per strip. She lines out and removes any sentences with incorrect details. She sorts into beginning, middle, and end and orders the sentences in each block in the most logical order.

We work in improving narrations in other ways. Sometimes, I find her sentences too brief in content. When I type them, I leave blanks for her to add more detail. I call this making a sentence better. One day, Pamela, inspired to go above and beyond the call of duty, narrated forty-nine sentences. Some sentences repeated the same information, one more detailed than the other. I showed her how to choose the better sentence.

After we finish, I paper clip all the sticky notes and sentence strips in one bag and store them in a Ziploc bag. This helps me to store her work in an organized manner.

At this point, I am scaffolding Pamela by writing everything for her on the stick notes. The first step in the transition will be for her to write the final narration all by herself. Then, I plan to turn over the responsibility for writing all the notes, one column at a time.

Every day, we focus on one very simple story from the syntax-controlled primers recommended by Dubard for the association method. While these are not living books, they are what Pamela needs to develop enough syntax to narrate living books. I see them as a bridge that helps her go from where she is to where I hope she will be. The first thing we do is to look at the story's words listed at the beginning of the primer (a discovery Pamela made!). In the story "Boo Jumps", the new words are animal sounds (urp, bow-wow, meow), and the reinforced words are many. Pamela also studies the title page, which is always illustrated. We record her predictions on one sticky note and predicted vocabulary on another before we ever read the story (you can click the picture to see it enlarged). In this story, Pamela predicts very reasonable possibilities: (1) Boo jumps, (2) Boo jumps on the fence, and (3) the animals can chase. She predicts words like fence, Boo, jumps, bow-wow, meow, and urp.

Then, she reads the story aloud to me one time (a single, hopefully attentive reading). After the reading, Pamela orally narrates the story. I film her to avoid slowing her down and listen to the recording to write it and post it on the board. As I write, I sort between sentences that are literal (drawn from the text or illustrations) and sentences that are interpretive. In this narration, Pamela incorrectly sequenced the story, placing Boo's jump before the animals making sounds. The frog makes a sound after the cat and dog jump on the fence (not before). This was the literal part of her narration:

Boo jumps. Boo jumps on the branch. The cat makes a sound. The dog says, "Bow-Wow!" The cat says, "Meow!" The frog says, "Urp!" The cat jumps on the fence. The dog jumps on the fence. The branch breaks. Boo falls.

Pamela included this bit of interpretive thinking in her narration:

Boo says, "Boo!" Boo is not hurt. Boo does not need a doctor.

I place a sticky note with her literal sentences in her narration in the column labeled Understanding and the inferred sentences under Interpretation. One weakness I have observed is that Pamela has difficulty ordering sentences in the correct sequence in her narrations, which is logical since she has difficulty in sequencing words because of her aphasia:

Once she finishes her oral narration, we study her predictions and line out any that were wrong. I make a point to congratulate her for thinking of such wonderful ideas. I am learning that Pamela is a champion at connecting these stories to her own life. This story reminded her of sitting in a tree when she was a little girl, and the dog reminded her of a dog we owned at that time of her life. Making connections comes naturally to Pamela. She makes hardly any connections to other books and stories, and that is what I will be encouraging whenever possible.

At this point of the process, we transition to how we have always done the association method. She and I read a script to practice new syntax and maintain mastered syntax: I read the questions and she, the answers; then, we swap roles; finally, I ask questions and she answers them without peeking. She does her copywork, written narration, and dictation plus worksheet activities that involve explaining why things belong in the same group, looking at a picture and writing her own questions and answers, filling in the blank and answering questions with the focus on correct syntax, and sequencing pictures from the story. Since Pamela finds sequencing difficult, I show her how to break up every story into a beginning, middle, and end. She is much better at sequencing during a narration when she fixes the story's arc in her mind.

The animals are the focus of the beginning of the story.

The middle is Boo's arrival and fall.

The story concludes with Boo and his friends sitting under the tree.

The final step of the Go! Chart is one last oral narration. Nearly every time, Pamela's narrations show great improvement in this final step. Pamela retells the story without peeking or looking at any pictures.

A fence is beautiful. A cat meows. The cat sits on the fence. A dog barks. The cat meows. A frog says, "Urp!" The frog sits on the grass.

Boo says, "Boo!" Boo stands on a branch. Boo falls. Boo is stuck. Boo runs.

Some animals are happy. Some animals see Boo. Some animals see Boo and a broken branch. Boo is happy.

At this point, I often see ways to improve Pamela's narrations further. While she usually correctly sequences the big picture, the little details are sometimes in the wrong order. Borrowing an idea from Cheri Hedden, I type up the narration, one sentence per line. Then, I cut it into strips, one sentence per strip. She lines out and removes any sentences with incorrect details. She sorts into beginning, middle, and end and orders the sentences in each block in the most logical order.

We work in improving narrations in other ways. Sometimes, I find her sentences too brief in content. When I type them, I leave blanks for her to add more detail. I call this making a sentence better. One day, Pamela, inspired to go above and beyond the call of duty, narrated forty-nine sentences. Some sentences repeated the same information, one more detailed than the other. I showed her how to choose the better sentence.

After we finish, I paper clip all the sticky notes and sentence strips in one bag and store them in a Ziploc bag. This helps me to store her work in an organized manner.

At this point, I am scaffolding Pamela by writing everything for her on the stick notes. The first step in the transition will be for her to write the final narration all by herself. Then, I plan to turn over the responsibility for writing all the notes, one column at a time.

Friday, June 22, 2007

Improving Reading Comprehension (Model)

In my introduction to "Improving Reading Comprehension", I narrated background information Jennifer Spencer provided about (1) five kinds of long-term memory, (2) Charlotte Mason's understanding of memory, (3) strategies for getting facts and information into long-term memory, (4) assessing reading comprehension, and (5) sources of three models of retelling/narration. Jennifer did not explain Charlotte Mason's model because Charlotte Mason educators were her audience, so I concluded with links to Charlotte Mason's writings about narration. In this blog post, I will describe the other two models plus Jennifer's hybrid and the results of her research. In my next blog post, I will narrate how I have applied her very practical session at home.

The first book Jennifer reviews is Read and Retell by Hazel Brown and Brian Cambourne. This book contains thirty-eight examples of descriptive, persuasive, argumentative, explanatory, and instructive writing. It outlines four steps in narration. First, teachers build a background by encouraging students to think forward to the story and predict the content, vocabulary words, and phrases based on the title of the story. Second, students read the text, orally or silently. Third, students retell the story in writing without peeking. Fourth, students in small groups share and compare retellings, figuring out how they differ from each other and differ from the texts. Then, they rewrite their narrations fixing altered meaning, omitted details, borrow ideas from other narration, etc.

Jennifer explains several aspects of this approach that seemed out of line with Charlotte Mason principles. She thought the method seemed artificial, not organic to the process of reading to know and telling what is known. The passages selected by the authors are not as literary as Charlotte Mason would have recommended. Moreover, Charlotte preferred whole, living books to excerpts and highlights. Finally, students are encouraged to reread the text, while Charlotte Mason emphasized a single reading.

Jennifer favored the second book in developing her hybrid model of teaching four aspects of narration (sequencing, connecting, interpreting, and narrating): The Power of Retelling. This developmental model of retelling enables children to add abstract, critical, and inferential thinking to their narrations. Developmentally appropriate strategies cover four stages: pretelling, guided retelling, story map retelling, and written retelling. The pretelling step is just like the first step of the earlier model (predicting content, words, and phrasing). In the guided retelling stage, teachers use concrete techniques to explain the structure of stories, identify elements of the story, and build background knowledge with related books. They also model narration for the students. In the story map retelling stage, teachers show student how to use abstract tools like graphic organizers to see patterns and highlight relationships between parts versus the whole, personal experiences, and various comparisons. This step enables students to move beyond exact retellings. The written retelling stage is very similar to the process explained in the earlier book. If this approach intrigues you and the book does not satisfy your hunger, one of the co-authors, Vicki Benson, holds seminars!

Jennifer's hybrid model includes living books and allows a single attentive reading. She chooses whole novels and builds background knowledge through picture storybooks and nonfiction trade books related to the novel. She recommends working through the developmental stages outlined in The Power of Retelling. She finds the best graphic organizer for retelling is a six-column Go! Chart with columns for prediction, vocabulary, understanding, interpretation (abstract ideas, theme, real meaning, tone, symbolism, inference), connection (with the phrase "__________ reminds me of __________ because __________), and retelling (beginning, middle, end). Her students write their ideas on sticky notes and place them on the chart. First, her students record pretelling in the first two columns (prediction and vocabulary). Next, they read the story and write notes on their literal understanding and interpretation in the next two columns (understanding and inference). They make connections and justify them in the connections column. They review their predictions, take down any wrong ones, and make new ones for future chapters. Then, they retell the story, keeping clear the beginning, middle, and end of the chapter. Finally, they create a comic strip with one square for each chapter to guide them when they write a narration of the entire novel at the end of the last chapter. Jennifer also encourages parents to hear ten minutes of reading aloud every day.

Jennifer flies through the results of the three areas measured by the Ekwall-Shanker Reading Inventory (oral reading accuracy, oral reading comprehension, and silent reading comprehension). After the pretest, she spent twelve weeks applying these ideas with a fourth grade class reading the novel Little Women. Then, she retested after twelve weeks and observed a leap of one to two grade levels in all three areas assessed.

In my final blog post about this breakout session, I plan to show how we are applying Jennifer's model at home.

The first book Jennifer reviews is Read and Retell by Hazel Brown and Brian Cambourne. This book contains thirty-eight examples of descriptive, persuasive, argumentative, explanatory, and instructive writing. It outlines four steps in narration. First, teachers build a background by encouraging students to think forward to the story and predict the content, vocabulary words, and phrases based on the title of the story. Second, students read the text, orally or silently. Third, students retell the story in writing without peeking. Fourth, students in small groups share and compare retellings, figuring out how they differ from each other and differ from the texts. Then, they rewrite their narrations fixing altered meaning, omitted details, borrow ideas from other narration, etc.

Jennifer explains several aspects of this approach that seemed out of line with Charlotte Mason principles. She thought the method seemed artificial, not organic to the process of reading to know and telling what is known. The passages selected by the authors are not as literary as Charlotte Mason would have recommended. Moreover, Charlotte preferred whole, living books to excerpts and highlights. Finally, students are encouraged to reread the text, while Charlotte Mason emphasized a single reading.

Jennifer favored the second book in developing her hybrid model of teaching four aspects of narration (sequencing, connecting, interpreting, and narrating): The Power of Retelling. This developmental model of retelling enables children to add abstract, critical, and inferential thinking to their narrations. Developmentally appropriate strategies cover four stages: pretelling, guided retelling, story map retelling, and written retelling. The pretelling step is just like the first step of the earlier model (predicting content, words, and phrasing). In the guided retelling stage, teachers use concrete techniques to explain the structure of stories, identify elements of the story, and build background knowledge with related books. They also model narration for the students. In the story map retelling stage, teachers show student how to use abstract tools like graphic organizers to see patterns and highlight relationships between parts versus the whole, personal experiences, and various comparisons. This step enables students to move beyond exact retellings. The written retelling stage is very similar to the process explained in the earlier book. If this approach intrigues you and the book does not satisfy your hunger, one of the co-authors, Vicki Benson, holds seminars!

Jennifer's hybrid model includes living books and allows a single attentive reading. She chooses whole novels and builds background knowledge through picture storybooks and nonfiction trade books related to the novel. She recommends working through the developmental stages outlined in The Power of Retelling. She finds the best graphic organizer for retelling is a six-column Go! Chart with columns for prediction, vocabulary, understanding, interpretation (abstract ideas, theme, real meaning, tone, symbolism, inference), connection (with the phrase "__________ reminds me of __________ because __________), and retelling (beginning, middle, end). Her students write their ideas on sticky notes and place them on the chart. First, her students record pretelling in the first two columns (prediction and vocabulary). Next, they read the story and write notes on their literal understanding and interpretation in the next two columns (understanding and inference). They make connections and justify them in the connections column. They review their predictions, take down any wrong ones, and make new ones for future chapters. Then, they retell the story, keeping clear the beginning, middle, and end of the chapter. Finally, they create a comic strip with one square for each chapter to guide them when they write a narration of the entire novel at the end of the last chapter. Jennifer also encourages parents to hear ten minutes of reading aloud every day.

Jennifer flies through the results of the three areas measured by the Ekwall-Shanker Reading Inventory (oral reading accuracy, oral reading comprehension, and silent reading comprehension). After the pretest, she spent twelve weeks applying these ideas with a fourth grade class reading the novel Little Women. Then, she retested after twelve weeks and observed a leap of one to two grade levels in all three areas assessed.

In my final blog post about this breakout session, I plan to show how we are applying Jennifer's model at home.

Thursday, June 21, 2007

Improving Reading Comprehension (Introduction)

The plenary sessions I have narrated so far involve abstract thinking about the meaning of Charlotte Mason's principles with respect to assessment. The talk on geography also focused more on ideas rather than practical application. Breakout sessions are usually more concrete with an emphasis on how to implement her ideas. The first one I attended was exactly that, for I walked out of the classroom with techniques that I am already using in real life! Because my notes on this one are copious, I have broken the narration into two segments (Introduction and Model), followed up a blog post about my experience with her model to date.

Jennifer Spencer, the Assistant Director of The Village School, spoke about a research project she did to complete her master's degree from Gardner-Webb University. She called this session, "Improved Reading Comprehension through Retelling". She begins by turning to research covered in the book Brain Matters by Patricia Wolfe. Charlotte Mason's primary educational habit to form was the habit of attention, which is not an easy task when you realize that the brain discards ninety-nine percent of stimuli with fifteen seconds. (I thought to myself that it is no wonder too much sensory input overwhelms autistic children!) She reminds us that Charlotte Mason hinted at the difference between long-term and short-term memory (the inner place and the outer court). In case you are curious, I found a wonderful quote on page 257 of Volume 6:

Jennifer explains that our long-term memory has five kinds of storage (like files in a filing cabinet). She mentions two, semantic and emotional memory. Semantic memory, the focus of the teaching profession, involves facts and information not associated with events in one's life and is most difficult to retain. On the other hand, emotional memory, the most powerful, derives from emotionally charged events in one's life.

I would like to add how fascinating this information to me from the perspective of Relationship Development Intervention. The link I found furthered my understanding of memory, which comes in two forms, non-declarative and declarative. The former is the kind of memory that is recalled non-verbally, while the latter is recalled in words. Non-declarative memory comes to people much more readily: procedural memory (blowing bubbles with gum or candlewicking), motor skill memory (procedural memory so well-learned that it no longer requires any thought--did you ever reach the store and not recall actually driving there?), and the emotional memory (discussed in the last paragraph). Declarative memory requires the recall of facts and information, the domain of schools. It has two forms, episodic memory and semantic memory. Episodic memories derive from events that happen in our lives at a specific time and place and are most powerful when anchored by emotion. When taught with traditional methods (oral lessons and emotionally dry textbooks lacking storytelling), semantic memory require practice and review for facts and information to make it to long-term memory.

Please humor me with one more rabbit trail before turning back to Jennifer's session. In the passage quoted earlier, Charlotte Mason observed difficulties we have in storing information in semantic memory. After we read the newspaper, "Details fail us, we can say,––'Did you see such and such an article?' but are not able to outline its contents." Teachers give an oral lesson, and "We try to remedy this vagueness in children by making them take down, and get up, notes of a given lesson: but we accomplish little." She noticed information is lost most readily when it "leaves the patient, or pupil, unaffected." Charlotte sprinkles her writing with hints at the marks of a fit book that stirs the souls of pupils by making an emotional connection.

Jennifer then talks about ways to improve the chances of facts and information making it to long-term memory. One way to support semantic memory is to tap into emotional memory by forming emotional connections and episodic memory by setting up events related to the knowledge. Acting out a passage, building models, getting first-hand knowledge, taking field trips and using graphic organizers are all ways to support semantic memory. The mind must connect new ideas to prior knowledge ala the law of association (page 157), forming links in a chain of memories. Studies show that peer teaching (group narration), summarizing and paraphrasing (Volume 3, page 180), and self-asking (Volume 3, page 181) all grow dendrites in the brain.

Jennifer addresses the relationship between reading comprehension and retelling (narration). She discusses several problems that crop up when assessing reading comprehension. First, successful decoding does not automatically mean the student comprehends the material. Decoding does not reflect understanding with accuracy. Second, traditional "thinking" questions cause the question writer to think more deeply than the child. Charlotte agreed, quoting a philosophical friend of hers, "The mind can know nothing save what it can produce in the form of an answer to a question put to the mind by itself" (Volume 6, page 16).

If decoding and answering clever questionnaires does not reveal comprehension, then what does? Jennifer cites research that a child shows comprehension in how he evaluates, organizes, and presents ideas from a reading passage. Retelling reveals all three of these skills! It requires students to sequence events, connect ideas with background knowledge, recognize and interpret clues in the reading, and construct a cohesive narrative. Jennifer explains that she wanted to see if teaching students these four processes (sequencing, connecting, interpreting, and narrating) is positively correlated with increased reading comprehension scores on standardized tests. (Yes, Virginia, even private school teachers and homeschoolers often find it hard to escape this bogie.)

To see if learning to narrate is positively correlated with improved reading comprehension scores, Jennifer explains she found ways to measure comprehension and to teach processes required in narration. For a pretest and post-test, she collected three narrations from students in a fourth grade class and performed tests from the Ekwall-Shanker Reading Inventory, which contains thirty-eight diagnostic tests in eleven different areas. She selected the oral and silent reading subtest, which assesses oral reading accuracy, oral reading comprehension, and silent reading comprehension. The test tops out at an eighth grade reading level and a couple of students needed higher-level material. She also presented two rubrics made with a free Internet program, Rubistar, to help her score the narrations.

Jennifer explains how she developed developed a hybrid model of how to teach processes required in narration based on three sources: Charlotte Mason (Volume 1, Volume 3, and Volume 6), Read and Retell by Hazel Brown and Brian Cambourne, and The Power of Retelling by Vicki Benson and Carrice Cummins. In my next post about her model, I will explain the latter two models and the results of her research.

Jennifer does not spend much time discussing Charlotte Mason's view of narration because she knows her audience. In case you are new to Charlotte Mason, the following are links to many explanations of narration:

"Reading for Older Children" Volume 1, V, VIII Pages 226-230

"The Art of Narrating" Volume 1, V, IX Pages 231-233

"How to Use School-Books" Volume 3, Chapter 8

Sample Narrations from Examinations Volume 3, Appendix II

Results of Narration Volume 6, Introduction Pages 6-8, 15-17

Elementary Schools Volume 6, II, Chapter 1, Pages 241-248

Secondary Schools Volume 6, II, Chapter 2, Pages 259-261, 268-272

The following are links about the relationship between narration and the mind:

"Well-Being of Mind" Volume 6, I, Chapter 3, Pages 49-52

"Knowledge versus Information" Volume 3, Chapter 8, Pages 224-225

Literature Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 180-185

"Composition Comes by Nature" Volume 1, V, XIII, Page 247

Composition Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 190-192

Languages Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 211-213

"History Books" Volume 1, V, XVIII Pages 288-292

History Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 169-174

Geography Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section III, Page 227

Art Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 213-217

Citizenship Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 185-186

"Fitness as Citizens" Volume 3, Chapter 8, Page 88

Public Speaking Volume 6, I, Chapter 5, Page 86

The following are links about the relationship between narration and the soul:

"The Well-Being of the Soul" Volume 6, I, Chapter 3, Pages 63-65

"Method of Bible Lessons" Volume 1, V, XIV, Pages 251-252

"Knowledge of God" Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section I, Page 158-169

The following are links with Parents Review articles about narration:

Some Notes on Narration

Concerning "Repeated Narration"

Some Thoughts on Narration

We Narrate and Then We Know

Jennifer Spencer, the Assistant Director of The Village School, spoke about a research project she did to complete her master's degree from Gardner-Webb University. She called this session, "Improved Reading Comprehension through Retelling". She begins by turning to research covered in the book Brain Matters by Patricia Wolfe. Charlotte Mason's primary educational habit to form was the habit of attention, which is not an easy task when you realize that the brain discards ninety-nine percent of stimuli with fifteen seconds. (I thought to myself that it is no wonder too much sensory input overwhelms autistic children!) She reminds us that Charlotte Mason hinted at the difference between long-term and short-term memory (the inner place and the outer court). In case you are curious, I found a wonderful quote on page 257 of Volume 6:

But the mind was a deceiver ever. Every teacher knows how a class will occupy itself diligently by the hour and accomplish nothing, even though the boys think they have been reading. We all know how in we could stand an examination on the daily papers over which we pore. Details fail us, we can say,––"Did you see such and such an article?" but are not able to outline its contents. We try to remedy this vagueness in children by making them take down, and get up, notes of a given lesson: but we accomplish little. The mind appears to have an outer court into which matter can be taken and again expelled without ever having entered the inner place where personality dwells. Here we have the secret of learning by rote, a purely mechanical exercise of which no satisfactory account has been given, but which leaves the patient, or pupil, unaffected. Most teachers know the dreariness of piles of exercises into which no stray note of personality has escaped.

Jennifer explains that our long-term memory has five kinds of storage (like files in a filing cabinet). She mentions two, semantic and emotional memory. Semantic memory, the focus of the teaching profession, involves facts and information not associated with events in one's life and is most difficult to retain. On the other hand, emotional memory, the most powerful, derives from emotionally charged events in one's life.

I would like to add how fascinating this information to me from the perspective of Relationship Development Intervention. The link I found furthered my understanding of memory, which comes in two forms, non-declarative and declarative. The former is the kind of memory that is recalled non-verbally, while the latter is recalled in words. Non-declarative memory comes to people much more readily: procedural memory (blowing bubbles with gum or candlewicking), motor skill memory (procedural memory so well-learned that it no longer requires any thought--did you ever reach the store and not recall actually driving there?), and the emotional memory (discussed in the last paragraph). Declarative memory requires the recall of facts and information, the domain of schools. It has two forms, episodic memory and semantic memory. Episodic memories derive from events that happen in our lives at a specific time and place and are most powerful when anchored by emotion. When taught with traditional methods (oral lessons and emotionally dry textbooks lacking storytelling), semantic memory require practice and review for facts and information to make it to long-term memory.

Please humor me with one more rabbit trail before turning back to Jennifer's session. In the passage quoted earlier, Charlotte Mason observed difficulties we have in storing information in semantic memory. After we read the newspaper, "Details fail us, we can say,––'Did you see such and such an article?' but are not able to outline its contents." Teachers give an oral lesson, and "We try to remedy this vagueness in children by making them take down, and get up, notes of a given lesson: but we accomplish little." She noticed information is lost most readily when it "leaves the patient, or pupil, unaffected." Charlotte sprinkles her writing with hints at the marks of a fit book that stirs the souls of pupils by making an emotional connection.

A book may be long or short, old or new, easy or hard, written by a great man or a lesser man, and yet be the living book which finds its way to the mind of a young reader. (Volume 3, page 178)

There is never a time when they are unequal to worthy thoughts, well put; inspiring tales, well told. Let Blake's Songs of Innocence represent their standard in poetry DeFoe and Stevenson, in prose; and we shall train a race of readers who will demand literature--that is, the fit and beautiful expression of inspiring ideas and pictures of life. (Volume 2, page 263)

Jennifer then talks about ways to improve the chances of facts and information making it to long-term memory. One way to support semantic memory is to tap into emotional memory by forming emotional connections and episodic memory by setting up events related to the knowledge. Acting out a passage, building models, getting first-hand knowledge, taking field trips and using graphic organizers are all ways to support semantic memory. The mind must connect new ideas to prior knowledge ala the law of association (page 157), forming links in a chain of memories. Studies show that peer teaching (group narration), summarizing and paraphrasing (Volume 3, page 180), and self-asking (Volume 3, page 181) all grow dendrites in the brain.

Jennifer addresses the relationship between reading comprehension and retelling (narration). She discusses several problems that crop up when assessing reading comprehension. First, successful decoding does not automatically mean the student comprehends the material. Decoding does not reflect understanding with accuracy. Second, traditional "thinking" questions cause the question writer to think more deeply than the child. Charlotte agreed, quoting a philosophical friend of hers, "The mind can know nothing save what it can produce in the form of an answer to a question put to the mind by itself" (Volume 6, page 16).

If decoding and answering clever questionnaires does not reveal comprehension, then what does? Jennifer cites research that a child shows comprehension in how he evaluates, organizes, and presents ideas from a reading passage. Retelling reveals all three of these skills! It requires students to sequence events, connect ideas with background knowledge, recognize and interpret clues in the reading, and construct a cohesive narrative. Jennifer explains that she wanted to see if teaching students these four processes (sequencing, connecting, interpreting, and narrating) is positively correlated with increased reading comprehension scores on standardized tests. (Yes, Virginia, even private school teachers and homeschoolers often find it hard to escape this bogie.)

To see if learning to narrate is positively correlated with improved reading comprehension scores, Jennifer explains she found ways to measure comprehension and to teach processes required in narration. For a pretest and post-test, she collected three narrations from students in a fourth grade class and performed tests from the Ekwall-Shanker Reading Inventory, which contains thirty-eight diagnostic tests in eleven different areas. She selected the oral and silent reading subtest, which assesses oral reading accuracy, oral reading comprehension, and silent reading comprehension. The test tops out at an eighth grade reading level and a couple of students needed higher-level material. She also presented two rubrics made with a free Internet program, Rubistar, to help her score the narrations.

Jennifer explains how she developed developed a hybrid model of how to teach processes required in narration based on three sources: Charlotte Mason (Volume 1, Volume 3, and Volume 6), Read and Retell by Hazel Brown and Brian Cambourne, and The Power of Retelling by Vicki Benson and Carrice Cummins. In my next post about her model, I will explain the latter two models and the results of her research.

Jennifer does not spend much time discussing Charlotte Mason's view of narration because she knows her audience. In case you are new to Charlotte Mason, the following are links to many explanations of narration:

"Reading for Older Children" Volume 1, V, VIII Pages 226-230

"The Art of Narrating" Volume 1, V, IX Pages 231-233

"How to Use School-Books" Volume 3, Chapter 8

Sample Narrations from Examinations Volume 3, Appendix II

Results of Narration Volume 6, Introduction Pages 6-8, 15-17

Elementary Schools Volume 6, II, Chapter 1, Pages 241-248

Secondary Schools Volume 6, II, Chapter 2, Pages 259-261, 268-272

The following are links about the relationship between narration and the mind:

"Well-Being of Mind" Volume 6, I, Chapter 3, Pages 49-52

"Knowledge versus Information" Volume 3, Chapter 8, Pages 224-225

Literature Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 180-185

"Composition Comes by Nature" Volume 1, V, XIII, Page 247

Composition Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 190-192

Languages Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 211-213

"History Books" Volume 1, V, XVIII Pages 288-292

History Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 169-174

Geography Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section III, Page 227

Art Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 213-217

Citizenship Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section II, Page 185-186

"Fitness as Citizens" Volume 3, Chapter 8, Page 88

Public Speaking Volume 6, I, Chapter 5, Page 86

The following are links about the relationship between narration and the soul:

"The Well-Being of the Soul" Volume 6, I, Chapter 3, Pages 63-65

"Method of Bible Lessons" Volume 1, V, XIV, Pages 251-252

"Knowledge of God" Volume 6, I, Chapter 10, Section I, Page 158-169

The following are links with Parents Review articles about narration:

Some Notes on Narration

Concerning "Repeated Narration"

Some Thoughts on Narration

We Narrate and Then We Know

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

We Interrupt This Broadcast . . .

Yesterday, something exciting happened! Pamela taught herself how to blow bubbles with bubble gum. I didn't even know she was interested in mastering this fine art. Because her father is on the road, we filmed it so he could see her in action! She can blow even bigger bubbles, but, in this clip, she was chewing a new piece of gum!

Tuesday, June 19, 2007

"New" Handwriting Programs

My first narration of a breakout session from the conference will take another day or two, so I will share something interesting I read today on the Ambleside Online email list.

When I first began homeschooling, an occupational therapist, Nancy Kashman, gave me a copy of Handwriting without Tears, which turned out to be a great handwriting program for Pamela. Jan Olsen, also an occupational therapist and handwriting specialist, developed this style to allow children with fine motor delays to write with simpler letters and strokes. We were discussing this "new" handwriting program in our day, when a listmate recalled to our mind that Charlotte had discussed a "new" handwriting program in her day:

* Both have vertical lines.

* Both teach letters in an order based upon the strokes needed.

* Both start with what they considered to be the simplest strokes first.

* Both reduced the number of ornamental flourishes a letter had in comparison to other styles of the day.

Moreover, on pages 233 through 235 of Volume 1, Charlotte herself gave tips for teaching handwriting very similar to those used by Jan Olsen in her program, backed by modern research!

* "Let the writing lesson be short; it should not last more than five or ten minutes."

* "First, let him print the simplest of the capital letters with single curves and straight lines."

* "When he can make the capitals and large letters, with some firmness and decision, he might go on to the smaller letters––'printed' as in the type we call 'italics,' only upright,––as simple as possible, and large."

* "By-and-by copies, three or four of the letters they have learned grouped into a word––'man,' 'aunt'."

* "At this stage the chalk and blackboard are better than pen and paper."

* "Set good copies before him, and see that he imitates his model dutifully."

* "Do not hurry the child into 'small hand'; it is unnecessary that he should labour much over what is called 'large hand,' but 'text-hand,' the medium size, should be continued until he makes the letters with ease."

Compare Charlotte's advice to what Jan Olsen describes as advantages to her program and you will conclude what wonderful powers of observation Charlotte had: workbook design, teaching strategies, teaching method, time management, and research.

When I first began homeschooling, an occupational therapist, Nancy Kashman, gave me a copy of Handwriting without Tears, which turned out to be a great handwriting program for Pamela. Jan Olsen, also an occupational therapist and handwriting specialist, developed this style to allow children with fine motor delays to write with simpler letters and strokes. We were discussing this "new" handwriting program in our day, when a listmate recalled to our mind that Charlotte had discussed a "new" handwriting program in her day:

A 'New Handwriting.'--Some years ago I heard of a lady who was elaborating, by means of the study of old Italian and other manuscripts, a 'system of beautiful handwriting' which could be taught to children. I waited patiently, though not without some urgency, for the production of this new kind of 'copy-book.' The need for such an effort was very great, for the distinctly commonplace writing taught from existing copy-books, however painstaking and legible, cannot but have a rather vulgarising effect both on the writer and the reader of such manuscript. At last the lady, Mrs Robert Bridges, has succeeded in her tedious and difficult undertaking, and this book for teachers will enable them to teach their pupils a style of writing which is pleasant to acquire because it is beautiful to behold. It is surprising how quickly young children, even those already confirmed in 'ugly' writing, take to this 'new handwriting.'" (pages 235-236 of Volume 1)The parallels between a "new" handwriting program in our day to that of Charlotte's day are just amazing:

* Both have vertical lines.

* Both teach letters in an order based upon the strokes needed.

* Both start with what they considered to be the simplest strokes first.

* Both reduced the number of ornamental flourishes a letter had in comparison to other styles of the day.

Moreover, on pages 233 through 235 of Volume 1, Charlotte herself gave tips for teaching handwriting very similar to those used by Jan Olsen in her program, backed by modern research!

* "Let the writing lesson be short; it should not last more than five or ten minutes."

* "First, let him print the simplest of the capital letters with single curves and straight lines."

* "When he can make the capitals and large letters, with some firmness and decision, he might go on to the smaller letters––'printed' as in the type we call 'italics,' only upright,––as simple as possible, and large."

* "By-and-by copies, three or four of the letters they have learned grouped into a word––'man,' 'aunt'."

* "At this stage the chalk and blackboard are better than pen and paper."

* "Set good copies before him, and see that he imitates his model dutifully."

* "Do not hurry the child into 'small hand'; it is unnecessary that he should labour much over what is called 'large hand,' but 'text-hand,' the medium size, should be continued until he makes the letters with ease."

Compare Charlotte's advice to what Jan Olsen describes as advantages to her program and you will conclude what wonderful powers of observation Charlotte had: workbook design, teaching strategies, teaching method, time management, and research.

Monday, June 18, 2007

Rethinking Assessment

I attended Lisa Cadora's take on assessment, which was the second plenary session on Thursday morning, right after Amber's talk on geography. Last year, I did not have the opportunity to know Lisa in real life, but her 2006 breakout session entitled Charlotte Mason Meets Veggie-Tales helped me know how she deeply thinks. I have a confession to make . . . when I first read Veggie-Tales in the title, I flippantly scoffed and bypassed her session completely. However, when I actually spent time reading the description, I realized what a gem I had missed because of my complete ignorance (and arrogance)! I ordered the CD from SoundWord. Her talk helped me figure out why I felt a vague uneasiness about the Sunday school curricula I had seen all my life and enabled me to become a better Sunday school teacher. Because of the spiritual growth her talk inspired last year, I was eager to hear more from Lisa in real life.

Lisa calls her talk, "Knowing What Knowers Know: Rethinking Assessment for Human Learners". Lisa begins dramatically with a cold reminder of our collective experience with assessment, "We are weighed, measured, and found wanting" (a paraphrase of Daniel 5:27). This painful pronouncement reflects our culture's view of assessment: we wish to weigh and measure retention of information through examinations and a battery of tests. We nearly always end up finding our students wanting. This leads us to find our teachers, schools, and curricula wanting and, in an effort to escape blame, teachers catch themselves teaching to the test. If test scores continue to drop, then we toss the curricula and replace it with the new and improved curricula on the horizon, only to find ourselves in the same situation as few years down the road.

Americans have developed a theory that we can measure knowledge and knowers through standardized testing and hammer it into a reality of producing better-informed knowers. Charlotte Mason took a different tack: she hit upon narration, her primary assessment tool, by observing how children picked up and retained knowledge. Her observations led her discard oral lessons and textbooks and to favor reading living books. Experience teaching real-live knowers ruled out testing by standards and pointed her to assessing through narration. She refined her ideas by testing them out with students, striving to secure knowledge (children in the PNEU schools). Thus, she applied the exact opposite approach by observing reality and developing a theory based upon that reality.

Lisa Cadora points out factors that affect testing are not taken into account when using standardized tests to critique students, schools, teachers, and curricula. Some students might already know the material, so the educational environment had nothing to do with learning it. Likewise, the student might have learned it through other methods (tutor, self-education, etc.). Unfortunately, the students (and/or teachers) might have cheated. Many students might have simply memorized and promptly forgotten it after the test, a phenomenon covered by Frank Smith in some of his writings. (I called it "pump and dump" during my eighteen years of formal education!)

I would like to add two more factors to Lisa's list. First, we assume that the person who cannot meet the standards cannot reach certain goals. Temple Grandin could not learn algebra for she thinks in pictures and found nothing to visualize in the traditional instruction of algebra. She was told she could not be a cattle chute designer unless she earned a degree in engineering and that required her to master her mathematical nemesis. She settled for a doctorate degree in animal science. She ended up designing cattle chutes anyway: nearly a third of all cattle chutes in the United States are hers! Her chutes are innovative because she thinks of ways to make them more humane by imagining how a cow might perceive her equipment (and, thus, remain calm). Since she can visualize equipment in her mind just by looking at a blueprint (i.e., her brain works like a CAD), she is much more effective in quickly designing new plans. By the way, she pioneered a smaller version of a cattle chute to make a squeeze machine, a device used by autistic children to calm themselves.

The second factor I would add is how inaccurately tests measure achievement of these standards. When we lived in Pennsylvania, homeschool laws required that I test Pamela because her age would have made her a third grader. I reported her as first grade for math and reading based upon her abilities. I chose the Peabody Individual Achievement Test, which requires the child to point out the answers. Due to Pamela's expressive language delays, I thought this might be the best testing format for her. Wrong! The test ends when the child misses five questions in a row. The pre-kindergarten portion of the test required more knowledge of language than math: when shown a picture of a dime, she could say it was ten cents, but could not remember the word dime! She missed five questions in a row like that, so this standardized, normed test assessed someone who could add and subtract and count coins at a pre-kindergarten level! Three months later, I had her tested on the math portion of the WIAT, where she scored at a third grade level! She must have had a lucky day for I know she really was near the end of first grade in math.

Then, Lisa transitions to our official view of knowledge, the scientification of education. At the turn of the century, assessment of education shifted from the literary to a standardized, normed known product. We started to prize certainty over subjectivism, or, to quote Esther Meeks, we began "chasing the carrot of certainty." We take knowledge from the "Knower of All Knowers", God, and chop it up into tiny pieces. The teacher, "our showman to the universe" (page 188), spoon-feeds an isolated piece of knowledge to the student. The student focuses his whole attention on that isolated morsel of knowledge. Like blinders on a horse, the teacher blocks out all other related pieces of knowledge and cuts off access to the knower of all knowers.

At this point, Lisa presents an altered view of knowledge. In this case, knowledge is in its proper context and not chopped up into tiny pieces. Knowledge in this form exerts a force on our mind. Many things affect the student, a knower: the knowledge being studied, knowledge learned previously, other students, the teacher, and the Knower of All Knowers. Likewise, many things affect the teacher, who is also a fellow knower: the knowledge being studied, knowledge learned previously, the students, and the Knower of All Knowers. This model of knowledge is much more dynamic than the formulaic "official" view.

Lisa points out a great example of pursuing knowledge for its own sake from the 2007 Scripps Spelling Bee. An ESPN reporter was interviewing contestants before the bee began. When asked what he thought of the spelling bee, Evan M. O'Dorney disappointed the reporter by gushing about math and music, instead of spelling. In one press report, Evan explained,

Lisa concludes that Charlotte Mason, like Evan, knew the secret behind life-long learning,

In an earlier post, I mentioned that one expects a richer vocabulary after hearing Jack Beckman speak. Well, one thing I expect from Lisa Cadora is a longer book list: her session added four more books to mine!

* Book of Learning and Forgetting by Frank Smith (Book Review by Derrel Fincher)

* Personal Knowledge by Michael Polyani

* To Know as We Are Known by Parker Palmer (Book Review by Elizabeth Leborgne)

* Longing to Know by Esther Lightcap Meek