I think we owe it to children to let them dig their knowledge, of whatever subject, for themselves out of the fit book; and this for two reasons: What a child digs for is his own possession; what is poured into his ear, like the idle song of a pleasant singer, floats out as lightly as it came in, and is rarely assimilated. ~ Charlotte MasonWhat does "digging for" do to the mind?

The best way to answer that question is to dig for yourself. Until we experience digging, we can only see what our children show us. Digging takes time. It is a slow process. It demands careful attention. The results are not always immediate.

Understanding Charlotte Mason's method requires us to dig. Because we are used to having knowledge poured into us, opening her books and studying them is a challenge. It's much easier to read someone else's interpretation of her ideas or to follow a checklist or "how to". This may be easier but it runs the risk of becoming a system, the very thing Mason sought to avoid. We must understand why we do what we do.

Right now, I'm digging into The Living Page by Laurie Bestvater. If you're looking for a quick summer read, TLP is not it! I read a little bit and narrate to my commonplace journal. I copy my favorite quotes and phrases. I join the grand conversation about this book with AmblesideOnline friends.

This is how I process nature study (pages 17-27), which addresses Mason's connection to scouting, how Gilbert White inspired her, what Mason expected in a nature notebook, her thoughts about nature lists, scrapbooks, collections, a family diary, science notebooks, lab books, calendar of firsts, natural history clubs, etc. I read a page and write down my thoughts. I look up examples of nature notebooks at the digital archives. I write a collection of phrases resonating with me: "make Glory 'visible and plain,'" "source of delight," "knowing glory," and "traveling companions and life records."

Reflecting upon my walks at Santee National Wildlife Refuge, I copy Laurie's words, "Perhaps it was his ongoing relationship with a relatively small patch of country over time, allowing him to form deep knowledge of a particular place and to notice even the smallest seasonal changes that Mason admires" (page 20).

I let go of my guilt about the lapses in nature notebooking last winter and spring when I read what one of Mason's student teachers wrote, "I am horrified to find that I have not written in my diary for nearly a month" (page 21). I copy her words into my commonplace journal. Then, I pull out my nature notebook and make my first entry in six months! The skink in my watercolor is too short and stubby. The artists in my family would see every flaw. I remind myself of a recent article about John Ruskin: "So if drawing had value even when it was practised by people with no talent, it was for Ruskin because drawing can teach us to see: to notice properly rather than gaze absentmindedly. In the process of recreating with our own hand what lies before our eyes, we naturally move from a position of observing beauty in a loose way to one where we acquire a deep understanding of its parts."

I let go of my guilt about the lapses in nature notebooking last winter and spring when I read what one of Mason's student teachers wrote, "I am horrified to find that I have not written in my diary for nearly a month" (page 21). I copy her words into my commonplace journal. Then, I pull out my nature notebook and make my first entry in six months! The skink in my watercolor is too short and stubby. The artists in my family would see every flaw. I remind myself of a recent article about John Ruskin: "So if drawing had value even when it was practised by people with no talent, it was for Ruskin because drawing can teach us to see: to notice properly rather than gaze absentmindedly. In the process of recreating with our own hand what lies before our eyes, we naturally move from a position of observing beauty in a loose way to one where we acquire a deep understanding of its parts."

My goal is not to produce great art. My goals are to learn how to see, observe beauty in a skink, and understand its parts. Process, not product.

I think about the nature lists in the back of a notebook, which Laurie suggests students adapted to their own needs. I spend time in two states regularly and have a special walking place for both. Rather than sorting my items by kind (flower, bird, insect, etc.), I decide to sort mine by place. I get out my ruler and draw lines in the back of my notebook. Since I'm halfway through the notebook I begin my calendar with June 2014, rather than January. I make it a year and a half, rather than two. I leave a column for notes. I title it "Santee List." My first walk yields sixteen items: broad-headed skink (Eumeces laticeps), crane fly (tipulidae), eastern pondhawk dragonfly (Erythemis simplicicollis), roly poly (Armadillidium nasatum), daddy long-legs (Pholcus phalangioides), orchard orbweaver (Leucauge venusta), banana spider (Nephila clavipes), tiger beetle larva "chicken choker" (Cicindelinae), eastern tent caterpillar tent (Malacosoma americanum), catalpa leaf (Catalpa bignonioides), bald cypress wood (Taxodium distichum), unripened black cherries (Prunus serotina), sweet gum balls (Liquidambar styraciflua), huckleberry (or blueberry or...?), white blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium albidum), and naked puffball (Lycoperdon marginatum). Here's a video of the whacky crane fly.

Maybe, I'll attempt a calendar of firsts next spring.

I head over to AO's thread about this section of the book. One person asked about identifying and naming things. I write,

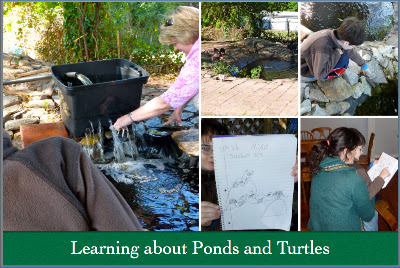

On learning the names of things, we take pictures and post them on Facebook. You would be amazed at how passionate the conversations between parents, grandparents, and knowledgeable friends get in naming things. If we don't know what something is, we give it our own pet name. There was this spider that we called either neon spiders or alien spiders and, one day, I got the perfect picture and we were able to name it: orchard orbweaver.Here are glimpses of Glory from our last walk.

I think it is healthy for children to realize that *WE* are lifelong learners. It's okay not to know something and to research it together. Our elementary students do spend some of their free time trying to find the name of something and it is exciting when they figure it out and share it with the class. Also, you sometimes need to see something several times and to watch it undergo seasonal changes and to observe its behavior before you can name it. It's the relationship that really matters, not the name. The name is just the icing on the cake.

Oh, the funniest thing is when you learn that something has no common name. Then, the kids start to debate what the name should be!