One

sign of autism in verbal children is handling pronouns incorrectly. When Pamela was in the stage of repeating everything she heard (immediate

echolalia), she would say, “Do you want cookies?” when she wanted cookies. Toddlers have echolalia as a normal part of language development, so it makes sense that autistic children parrot phrases. Because echolalia lasts much longer and occurs at a much older age in spectrum children, people worry about it. In Pamela’s case, I was excited she could say anything because she was non-verbal at age three!

As her grasp of language improved, she found pronouns so confusing she avoided them. She found it easier to speak in the third person, even about herself, much like some of our politicians. At this point in her development (from age seven and beyond), she would say, “Pamela want cookie.”

Pamela slowly started using pronouns and mixed them up in various ways, applying it to humans, reversing you and I, confusing he and she, avoiding we and they, etc. The most perplexing problem to overcome was distinguishing between first person, I, and second person, you. To observe this in action, one must pay close attention during one-on-one interactions with another person (usually, the child and parent) and one-on-one interactions between two other people (the parents or parent and siblings). Research shows that second-born children master I and you pronouns much more quickly than the firstborn does.

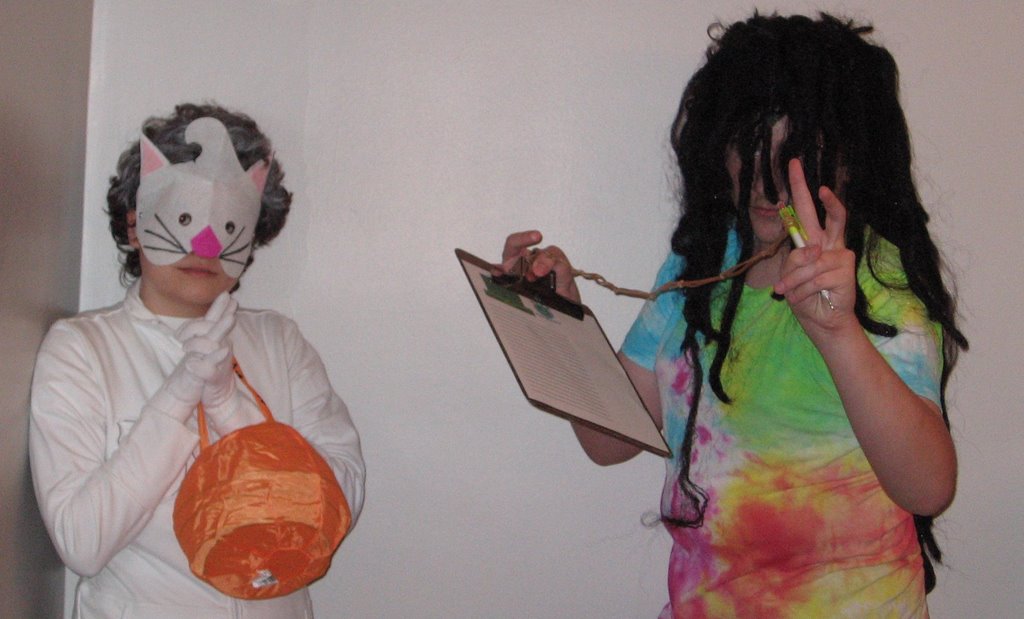

When Pamela mixes up her pronouns in conversation, I physically prompt her to sign them while she says them for an added visual cue: I, me, my, you, and your. I think the association method will offer the final solution in the long run because this form of mastering language introduces structure very slowly. The process of learning pronouns unfolds gradually (see page 10):

Repetitive Questions and Sentences: the only pronoun used in sentences is I and the only pronoun used in questions is you. These two pronouns are always in the nominative case (subject) to avoid confusion. Pamela learned to use proper names without the confusion of third person pronouns. Because she learned both questions and sentences, she practiced describing herself as I and the second person as you and hearing another person describe himself as I and Pamela as you. Because I always goes in sentences and you always goes in questions, her accuracy is much higher, boosting her confidence.

Animal Stories: Pamela continued to practice I and you only, solidifying her grasp of two and only two pronouns.

Inanimate Object Stories: The very next pronoun introduced is it, applied to all inanimate objects, but only in the nominative case (subject). At this point, Pamela showed great confidence in using I and you in the sentences and questions taught.

Personal Description Stories: By the time we made it to third person pronouns, Pamela felt secure in I and you. She spent one week applying he in the nominative case of a sentence and a second week on questions with he and did the same schedule for she. Then we devoted two more weeks using his in sentences and questions and two more with her. I introduced they and their at the same time, first in sentences and then in questions, because she seemed secure in applying possessive pronouns. By the time I added the possessive my into sentences only, Pamela understood the pattern and picked up the possessive form of the first person pronoun I quickly.

This week we are concentrating on the possessive your in questions only and Pamela is flying through the seven steps of her speech therapy. For every day, I have written stories about a different person: Monday (Mom—me), Tuesday (David—her brother), Wednesday (Opa—her grandfather), Thursday (Oma—her grandmother), and Friday (Dad—my husband). To emphasize who is supposed to be speaking, I have asked the person to read the sentences in response to questions asked by Pamela in the story. We follow that up with three rounds of questions in the following pattern: (1) Pamela asks; the second person answers; (2) the second person asks; Pamela answers; (3) Pamela asks; the second person answers; the second person asks; Pamela answers; Pamela asks. . .

To emphasize the concept of two people talking (Pamela and another person) in all of her written work (copywork, written narration, and dictation), she must label two columns to designate who is asking the questions and who is answering them. For this week, above the questions I wrote, “Pamela is talking” and above the sentences, “__________ is talking.”

This is more complicated than it seems because included in the mix is verb agreement between I/you/he/she/they and the verbs do/does, is/are, can, has/have, sees/see, and wants/want. Not to mention verb agreement having nothing to do with a possessive pronoun my/your/his/her/their and having everything to do with the noun in the subject!

I still need to introduce its and, because she is already aware of the contraction it's, I will probably spend the next week or two covering both words. You may notice I am ignoring we and our and other forms of first, second, and third person nouns. One thing I have learned from the association method is Pamela needs to be secure in what she has learned before adding more nuances! She is better off moving onto a fresh, completely unrelated concept like prepositions or present progressive language (is/are __________ing) than plowing into pronouns in greater detail. Constant review and generalization of previously mastered material in daily conversations allows her to solidify new concepts before plunging in further.

Time will tell how well Pamela generalizes keeping her pronouns straight in conversations. Right now, I am full of hope!